This past summer, every bookstore in New York City seemed to have a copy of Sofia Coppola’s photobook, a visual collection of all of her directing projects. Simply titled Archive, its sixty-five-dollar price tag deterred me from making an impulsive purchase, but its hot pink cover was too striking to pass by without at least taking a quick look. Many of the pictures are now instantly recognizable: seventeen-year-old Scarlett Johansson in Lost in Translation (2003), Kirsten Dunst powdered and coiffured in Marie Antoinette (2006), a decidedly Americanized Emma Watson in The Bling Ring (2013). But none were as arresting as those of The Virgin Suicides (1999), Coppola’s directorial debut and arguably one of her most highly regarded projects to this day. The four, beautiful, blond Lisbon girls and their world of white bedroom curtains and suffocating American suburbia are captured in hazy film on dozens of pages. As I flipped through them, I couldn’t help but be reminded of another family of American girls, conceived more than a century before Jeffrey Eugenides wrote about the Lisbon sisters.

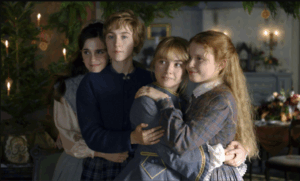

Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women is perhaps one of the earliest and most well-known novels to tackle the construction of the all-American girl. With the characters of Meg, Jo, Beth and Amy March, Alcott created four of the most beloved models of American girlhood to this day. The novel has inspired over seven major film adaptations since its publication, the most recent of which grossed over $200 million worldwide. Adapted from Jeffery Eugenides’s 1993 novel, The Virgin Suicides (1999), too, earned critical acclaim upon its release and has only become more popular over time, quickly becoming a cult classic.

What is it about these stories that so appeal to us? Alcott and Eugenides captured the American imagination long before these narratives were adapted for the screen. What is so interesting about the March sisters and the Lisbon sisters? These stories about these rather ordinary girls, chronicling the everyday pleasures and pains of sisterhood and female adolescence?

More importantly, why do more than half of them end up dead?

Let us return to the novels themselves. Upon initial evaluation, it seems that the March girls and the Lisbon girls could not be more different. Little Women begins on Christmas Eve, with an image of Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy sitting in a warm and cozy home, “knitting away in the twilight, while the December snow fell quietly without, and the fire crackled cheerfully within.” The first few sentences of The Virgin Suicides, on the other hand, are as follows: “On the morning the last Lisbon sister took her turn at suicide— it was Mary this time, and sleeping pills, like Therese— the two paramedics arrived at the house knowing exactly where the knife drawer was, and the gas oven, and the beam in the basement from which it was possible to tie a rope.” From the very first sentence of the novel, the Lisbon girls are already dead.

Thirteen-year-old Cecilia Lisbon takes her own life within the first few chapters, and the rest of the novel is framed by this tragedy. The already strict and deeply religious Lisbon household becomes even more suffocating for Cecilia’s sisters in the wake of her death. As a boy in their neighborhood puts it, “You would’ve killed yourself just to have something to do.” But Bonnie, Therese, Mary, and Lux Lisbon are not passive, silent, depressed creatures. Therese goes to Science Club meetings, Mary sews costumes for the school play, Bonnie attends local Christian fellowship meetings, and Lux sings in the school musical. All four of them are ecstatic to go to the school dance, during which Therese explains to her date, “Cecilia was weird, but we’re not… We just want to live. If anyone would let us.” They are dynamic, complicated characters struggling for liberation— trying their utmost to, in fact, live.

The March sisters, too, dream of freedom. We learn about their “castles in the air”, their greatest ambitions, in great detail. Meg dreams of a beautiful, luxurious, home that she is “to be mistress of” and manage as she pleases. Beth wants to forego marriage and instead dreams of staying home with her parents, Marmee and Mr. March, forever. Jo dreams of being a famous writer. Amy wants to live in Rome and “be the best artist in the whole world.” All four girls dream of independence, comfort, and self-fulfillment. Jo and Amy’s dreams of glory and fame in the public sphere in particular demonstrate that they are girls with serious aspirations, equal to those of young men.

But what becomes of these girls, the Marches and the Lisbons, and all their hobbies and aspirations? The Lisbon sisters, unable to break free from their abusive parents and the repression of their quietly suffocating suburban town, are driven to the drastic measure of ending their lives on Earth. Beth dies of illness. Meg, Jo, and Amy give up on their castles in the air, marry, and become mothers. Of course, the decision to become a wife and mother is by no means problematic in and of itself. The issue lies in how the narrative ultimately seems to reinforce Marmee’s point of view: “To be loved and chosen by a good man is the best and sweetest thing which can happen to a woman.” Not only is it an outdated idea, it is one that actively kills the versions of the women her daughters could have become.

By the end of the novel, the formerly ambitious and tomboyish Jo remarks that she is happy to wait to write her book, or never get around to it at all. The ways in which the stories of the March sisters conclude illustrates a disheartening reality: All girls must die if they are to become grown (no longer ‘little’) women. Meg, Jo, and Amy bury their girlhood under lost dreams and the weight of gender norms and social expectations. Sweet, irreproachable Beth dies in her sleep, eternally young. And the Lisbon girls, trapped in a world that prevents their development and self-actualization at every turn, never get to grow up.

So the question of female liberation for the Marches and the Lisbons remains ambiguous. Three of the four March sisters settle into traditional roles, their youthful aspirations to wealth, success, and fame largely discarded. The stories of the Lisbon sisters follow Beth March’s trajectory, their early deaths dooming them to eternal girlhood. None of the nine girls are able to achieve true freedom, independence, or self-actualization.

And yet, I love them all— and I am not alone. Female filmmakers are drawn to their voices and their worlds. Millions of girls all over the world will continue to read about the March and Lisbon girls, will relate to their youth and their experiences of adolescence, will pick a favorite sister and nurture a soft spot for this fictional personality forever. As someone who grew up with a younger sister and several younger cousins (all girls), I’ve revisited these two books a dozen times over. Both Alcott and Eugenides take great care in developing their protagonists into compelling characters, challenging their audience to view these young women as complex, three-dimensional, individuals. In doing so, they complicate the portrait of American girlhood, and most importantly, continue to give readers someone to root for.