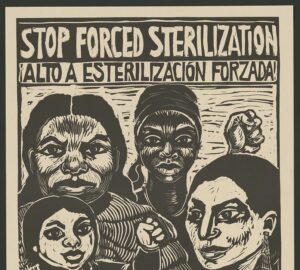

The concept of breeding is nothing new to us. Designer dogs are bred to make perfect pets and stately show animals. Millions are spent in the pursuit of the two fastest Thoroughbreds who will breed the next Kentucky Derby winner. But what about the breeding of humans? Some believe our genetic code dictates how we will behave, and that our genetics should take precedence over our own sense of agency and desire for familial life. These questions were central to the eugenics movement, often through the forced sterilization of marginalized populations. If that makes you shudder, consider this: it still happens today.

In 1883, Sir Francis Galton coined the term “eugenics,” derived from the Greek roots meaning “good birth.” Galton was a British sociologist and half-cousin of Charles Darwin who sought to apply principles from Darwin’s “On the Origin of Species” to humans. Eugenics is the theory that the human race can be improved through the strategic “breeding” of people, and that only those with ‘desirable traits” should reproduce–criminals or any people who are poor, unintelligent, ugly, or disabled should refrain from reproducing in the hope that their qualities are removed from the human gene pool.

The eugenics movement took hold in Europe and America in the early 1900s. 32 American states adopted federally-funded sterilization programs, carrying out approximately 60,000 sterilizations that above all targeted African American, Latina, and Native American women. Nazi Germany has a particularly nasty history with eugenics, beginning with the T-4 euthanasia movement from 1939 to 1941. During this series of killings, which continued in secret until 1945, over 200,000 “useless eaters,” such as mentally or physically disabled people, the elderly, and enemies of the state, were killed. One Nazi slogan read, “National Socialism is the political expression of our biological knowledge.”

Sterilization programs are alive and well today. In October 2016, in the Netherlands, the Rotterdam city council ruled that 160 women, all judged as unfit potential mothers due to “learning difficulties, psychological issues, or addiction,” should be given compulsory contraception by court order. The women were not criminals, but the city council’s welfare program had determined them to be unfit mothers. The council has listed 400 women to whom they will apply this contraceptive measure in the future.

In the United States, these programs also persist, but in secret. According to the Center for Investigative Reporting, “at least 148 female inmates in California received tubal ligations without their consent between 2006 and 2010.” The state justified these practices by noting that the $147,460 paid to the doctors performing the sterilizations was far less than “what you [spend] in welfare paying for these unwanted children,” assuming that the women planned to procreate and inhumanely ignoring their right to consent.

Presently, and despite debates on abortion and contraceptives, our country’s legal precedent is that every woman has agency over her reproductive rights. The right to privacy has been the subject of countless Supreme Court cases. For example, in the 1965 case Griswold v. Connecticut, which put an end to the “state prohibition against the prescription, sale, or use of contraceptives, even for married couples,” the right to privacy was granted for “intimate, personal matters such as childbearing.”

This clause of reproductive rights is included in the landmark 1972 Supreme Court case, Eisenstadt v. Baird, which ruled that unmarried individuals had the right to obtain contraceptives just as married couples could. Again, part of the winning argument was that each individual has the right to privacy. In the case, “Justice Brennan observed that ‘… [if] the right of privacy means anything, it is the right of the individual (emphasis added) [sic] married or single, to be free from unwanted governmental intrusions into matters so fundamentally affecting a person as the decision whether to bear or beget a child.’”

Though the United States Constitution does not directly grant or describe one unilateral right to privacy, rights to privacy are enforced by the First, Third, Fourth, and Fifth Amendments, according to the Supreme Court. In the watershed 1973 case Roe v. Wade, the Supreme Court also found that the “constitutional right to privacy entitles [a woman] to obtain an abortion freely.”

More generally, this notion of privacy is reiterated by Article 12 of the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights: “No one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to attacks upon his honor and reputation. Everyone has the right to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks.” In other words, government interference with reproductive rights could be considered interference with both individual privacy and familial matters.

If our country ignores this basic right to privacy when it comes to reproductive rights, we risk the creation of a slippery slope in which our practices, information, and home lives could also become subject to government control. These limitations would infringe upon the very definitions of liberty and personhood.

Now that human “breeding” is back in the courtroom, we are forced to consider the intersection of morality and legality. On May 15, 2017, Tennessee’s Judge Sam Benningfield signed a standing order allowing inmates to have their jail time reduced by 30 days in exchange for undergoing a birth control program: a free Nexplanon arm implant for women, preventing pregnancies for four years, and a vasectomy for males, a reversible surgery paid for by the Tennessee Department of Health. Benningfield claimed, “I hope to encourage them to take personal responsibility and give them a chance, when they do get out, to not to be burdened with children. This gives them a chance to get on their feet and make something of themselves.”

While Benningfield’s consideration of the inmates’ transition to post-jail life is an admirable one, it is still unethical to suggest that certain people are unworthy of reproducing. In addition, the assertion that criminal activity is hereditary is illogical. Crimes are caused first and foremost by individuals making inappropriate or harmful choices in the context of their own ever-changing environments. Furthermore, the systemic inequalities among races and classes make disadvantaged populations both more likely to commit crimes and more likely to be punished harshly for crimes. Thus, crimes are products of social environments more than they are products of DNA. Though some studies link DNA and brain activity to certain crime-linked traits such as antisocial behavior or aggression, these links are still tenuous given the complex nature of the human brain, the vast amount of tacit knowledge humans absorb every day from their environments, and the fact that children often inherit their parents’ behavioral patterns, too.

In May 2014, an interagency statement titled “Eliminating forced, coercive and otherwise involuntary sterilization” was released by groups including the World Health Agency and the United Nations. The statement “reaffirms that sterilization as a method of contraception and family planning should be available, accessible, acceptable, of good quality, and free from discrimination, coercion and violence.” It remains unclear what individual United States citizens can do to lend support to this cause.

As the United Nations and Supreme Court have both affirmed, reproductive rights belong to individuals, not to pseudoscientific and overly judgmental politicians pushing partisan agendas. The only situation in which it would be even remotely appropriate for the government to control human reproduction is through unilaterally applied population control measures that do not target individuals or groups. The earth is an overpopulated place, and if applying a unilateral limit on childbearing were scientifically proven to improve our quality of life and help our world, perhaps that would be a sacrifice we should all make. However, this is a policy that would be aimed at all humans. It simply does not matter how undesirable or undeserving a person may seem to you: if it’s their body, it’s none of your business.