During this remote semester, on-campus Bowdoin Rowers have been fortunate to be able to row together on the Androscoggin River. We typically row out of our Smith boathouse on the New Meadows River, so we are grateful for our opportunity to continue training out of the Merrymeeting boatyard in Brunswick during this unpredictable time. Through Merrymeeting we have been able to train our novices and varsity alike in single and double sculls. By practicing so much in small boats, our time on the Androscoggin has enabled us to make great technical improvement during a time in which we may have otherwise been unable to row at all.

Also incredible has been our opportunity to explore a brand new body of water – the beautiful Androscoggin River and Merrymeeting Bay. During this Indigenous Peoples’ Day, October 12, 2020, we want to acknowledge and better educate ourselves on the indigenous history of the Androscoggin River and the indigenous peoples that inhabited the lands around it.

We spoke with Professor Joseph Hall at Bates College, whose research and appreciation for indigenous peoples and histories led him to become involved in the Wabanaki place names project, which catalogs the names that indigenous groups gave to locations that they inhabited and interacted with.

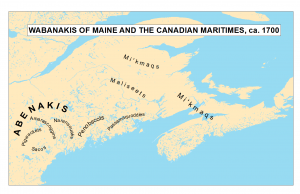

Wabanaki Place Names Map, from Professor Joseph Hall, Bates College

Place names give clues as to how a group interacted with the locations around them. The Wabanakis are a group of people that inhabited northern New England and eastern Canada. Wabanaki translates to “people of the Dawnland,” and the names of places they interacted with are indicative of how these people navigated Maine. Specifically, the names they assign to locations along the water indicate places of good portage or dangerous rapids. These give insight into how they moved throughout Maine and the northeast. Names assigned to land places often indicated favorable agriculture areas or gathering areas.

These names can inform us of the patterns of life of these groups. In the spring, Wabanakis caught migrating fish such as salmon at river waterfalls to eat. In the summer, growing conditions were favorable and Wabanakis would gather in riverside towns to grow crops. Such crops included corn, beans, and squash, and one such town they gathered in was Amarriscoggin, or Androscoggin. In the fall and winter, these groups would disperse from these towns to hunt animals such as deer and moose.

These seasonal migrations necessitated regular movements throughout the northeast. Rivers, such as the Androscoggin, were important routes that indigenous peoples used to travel efficiently. This travel was done by birchbark canoes, which were both strong and light. It was important for boats to be light so that travelers could circumvent dangerous portions of the rivers by carrying their boats through trails known as “portages. So the same waters that we have rowed on this semester were also navigated by indigenous Wabanaki during seasonal migrations to navigate between western and coastal Maine.

Place names might also point to crops or plants that were grown or found in those places. In fact, some research data suggests that the Merrymeeting Bay was so named after Wabanaki roots that translated to “wild rice bay” or “wild rice place.” Even today these grass-like wild rice plants may be seen along the shores of the Androscoggin as we row by.

As we educate ourselves on the indigenous histories of the lands we live on and the water we row on, it is important to acknowledge the modern-day implications of this history. While the past of our river is fascinating, our education does not stop at surface level trivia or curiosity about the people that once lived here. Indigenous populations were uprooted, aspects of their culture forgotten, and lands taken from them, and there are Wabanaki people that still inhibit Maine today. The history of these lands have profound current implications regarding rights of people who were historically uprooted from these areas. For this reason, this research must be done with great care, seeking the perspectives of indigenous people without burdening them. While learning about this history is meaningful and important, it is just a first step for creating respect and understanding towards the Greater Brunswick Community.