The neverending fight against fruit viruses has gotten even muddier. A recent study based out of Clemson University and the greater southern South Carolina area has made significant discoveries toward a better understanding of the role that pollinators play in pollen-borne plant viral transmissions. Prunus necrotic ringspot virus (PNRSV) and Prune dwarf virus (PDV) are pollen-borne viral infections that attack stone fruit crops worldwide, often greatly impacting the actual fruit yield. In the southeastern United States, the prevalence of PNRSV and PDV in peach crops and their mechanisms of virus spread are relatively unknown and under-studied. The researchers, Mandeep Tayal, Christopher Wilson, and Elizabeth Cieniewicz, studied the number of bees and thrips, small pollen-carrying insects, containing virus-positive pollen in peach orchards and the relationship to virus-positive pollen-carrying bees/thrips and their genus type.

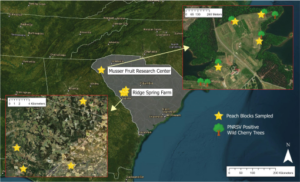

The researchers selected two orchards (see Figure 1), one with a higher suspected incidence of both PDV and PNRSV. Trees in each orchard were divided into blocks and then tested for PNRSV and PDV. Bees and thrips, two major pollinators of peach trees, are primarily active during peach bloom (from early March to early April). During the two years studied, bees and thrips were trapped using blue vane traps and sticky cards, respectively. Reverse Transcriptase-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) of RNA extracted from bee pollen and thrips was then used to detect either PNRSV or PDV.

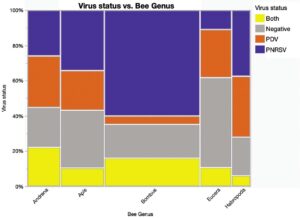

The researchers found different blocks of peaches had contrasting relative prevalences of the two viruses. In areas with largely PDV-infected trees, the majority of bees carried PDV-positive pollen, a phenomenon consistent throughout the different blocks. The virus and scope to which a block of trees was infected were directly proportionate to the number of bees carrying each virus-positive pollen. The researchers concluded that pollinators play an important role in spreading these viruses. From an ecological standpoint, they extrapolated that larger bees, such as Bumble and Blueberry Bees, could carry greater amounts of pollen and thus may have a larger impact on pollen-mediated viral infections (see Figure 2).

This is an important development for farmers and researchers alike. Both PNRSV and PDV have been previously known to be vertically integrated in stoned fruit generations; meaning viruses are passed on from parent to offspring. Given this, the primary strategy for combatting these viruses has been to cut down any infected trees. In theory, by sourcing uninfected juvenile saplings and cutting down the diseased trees, the spread and effect should be contained. Unfortunately, this tactic deteriorates with tree to tree transmission. The prevalence of horizontal integration adds a whole new dimension to the issue. As the virus is too common to be eradicated, a treatment that accurately targets and kills these viruses will likely be the only effective long term solution.

Pollinator-mediated viral infections, especially involving the physical mechanisms and driving ecological factors, are a highly under-researched field of biology. The aforementioned research simply scrapes the surface of all the possible driving forces and nuances surrounding this minimally understood process. Moreover, this information is concerning to both the peach industry and beyond. PDV and PNRSV not only diminish the product yield of stoned fruits, but they are also incredibly illusive and hard to treat. If infected pollen can not only be stored and transmitted by trees but also by pollinators, it makes containing the spread of such viruses remarkably challenging. Given the over half-billion industry that is just peaches alone, pollen-borne viruses represent a pressing matter. With farmers and biologists feeling the pressure to find a solution, it seems they will need to turn to new, innovative treatments.

References:

Amari K, Burgos L, Pallás V, Sánchez-Pina MA. Vertical transmission of Prunus necrotic ringspot virus: hitch-hiking from gametes to seedling. J Gen Virol. 2009 Jul;90(Pt 7):1767-1774. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.009647-0. Epub 2009 Mar 12. PMID: 19282434.

(Title Image) – Garvey, K. K. (2011, March 14). Peachy Keen – Bug Squad – ANR Blogs. UC ANR. Retrieved December 10, 2023, from https://ucanr.edu/blogs/blogcore/postdetail.cfm?postnum=4390

Hampson, CR, et al. “Prunus necrotic ringspot virus (almond bud failure) | CABI Compendium.” CABI Digital Library, 18 December 2021, https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/10.1079/cabicompendium.42426. Accessed 10 December 2023.

Mandeep Tayal, Christopher Wilson, and Elizabeth Cieniewicz “Bees and thrips carry virus-positive pollen in peach orchards in South Carolina, United States,” Journal of Economic Entomology 116(4), 1091-1101, (4 July 2023).

Peaches. (2023, February). Agricultural Marketing Resource Center. Retrieved November 12, 2023, from https://www.agmrc.org/commodities-products/fruits/peaches