Aging, also known as “senescence,” is an inevitable process in all living things. Organisms small and large eventually break down, accumulating enough wear and tear in their cells that ultimately causes the body to stop functioning as a whole. While medicine and lifestyle improvements stave off aging, identifying its fundamental causes has been more challenging. In January 2023, scientists in Dr. David Sinclair’s lab at Harvard Medical School published a paper with experimental evidence supporting what Sinclair calls the “Information Theory of Aging,” where damage to the epigenome can cause aging.

After receiving his Ph.D. in molecular genetics from the University of New South Wales, Sinclair completed his postdoctorate at MIT where he co-discovered the role of sirtuin enzymes in limiting age-related cellular damage in yeast. In addition to teaching genetics and translational medicine at Harvard Medical School since 1999, Sinclair authored the popular book Lifespan: Why We Age – and Why We don’t Have To (2019). His breakthroughs in the science of aging have earned him a great deal of attention from the public eye, resulting in appearances on several popular media outlets, including CBS’s “60 Minutes” and TIME magazine (The Sinclair Lab, 2023).

Sinclair’s newest discovery, published as “Loss of epigenetic information as a cause of mammalian ageing” in January 2023, focused on the role of epigenetics in aging. The title specifies that epigenetic information loss, rather than genetic information loss, is a cause of aging. Genetics refers to the raw molecular information sequences stored in cells as deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), which is physically condensed inside the nucleus into pairs of chromosomes. The material inside a chromosome is known as “chromatin.” The central dogma of molecular biology states that information in DNA sequences is read by the cell in the form of messenger RNA (mRNA) through transcription, and then ribosomes in the cell read this mRNA to make proteins through translation. DNA sequences that correspond to the production of a specific molecule are genes. The prefix epi- means “on top of,” so “epigenetics” refers to mechanisms that function “above” the molecules of DNA themselves, including reading DNA sequences, regulating gene transcription, and repairing mutated DNA. Like the DNA sequence, epigenetic changes are inheritable from parents to offspring.

The differences between genetics and epigenetics influence cellular reaction to damage. Damage to genes causes mutations, which are changes in the sequence of the DNA of that gene. Cells have mechanisms of repairing mutated DNA, but failure of these mechanisms can lead to cell death, or worse, cancer. Some DNA mutations, like those where a nucleotide is deleted, are irreversible.

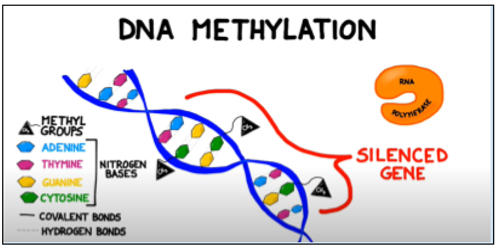

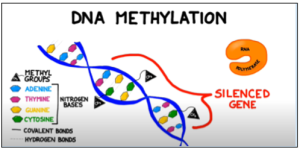

By contrast, epigenetic mechanisms are more easily reversed. One epigenetic mechanism is DNA methylation, where a methyl group (-CH3) is added to a cytosine nucleotide by the DNA methyltransferase enzyme. This extra functional group blocks transcription factors from binding to promoter regions nearby the methylated cytosine, in effect “silencing” the gene as it cannot be transcribed into mRNA. DNA methylation is important for differentiating cells into specific cell types by enabling cells to only express the most pertinent genes while still containing the entire genome (Moore et al., 2012). DNA methylation is reversible with the help of TET dioxygenase enzymes (Wu and Zhang, 2014). Geneticists have found DNA methylation to be a way to assess molecular aging in cells as a sort of “epigenetic clock”. By analyzing methylation patterns of the genome (the “methylome”), scientists can find the biological age as well as the rate of aging in an organism’s cells (Hannum et al., 2012).

Figure 1: Methyl groups attached to cytosine bases in a gene block the enzyme RNA polymerase from binding to the promoter region of a gene, preventing transcription. Adapted from BOGOBiology (2017)

Figure 1: Methyl groups attached to cytosine bases in a gene block the enzyme RNA polymerase from binding to the promoter region of a gene, preventing transcription. Adapted from BOGOBiology (2017)

To investigate how changes to the epigenome affect aging in mice, Sinclair used a mouse system with induced changes to the epigenome (ICE). The genetically modified mice had a higher frequency of double-strand breaks (DSBs) in the DNA, which cause changes in the epigenome as cells are required to use their mechanisms of DNA repair more often . Sinclair’s method reduced the frequency of mutations by breaking the DNA strands in a way that left more whole unpaired nucleotides in the severed strand, making it more difficult for the cell to repair the DNA strand with a different sequence than before. While ICE mice had no significant difference in mutation frequencies versus control mice, DSBs in specific locations of the genome were observed as expected (Yang et al., 2023). Thus, any apparent changes in aging in the ICE mice of this study could be ascribed to the epigenetic DSB changes rather than mutations.

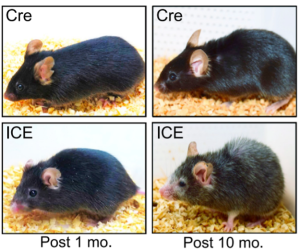

Figure 2: ICE treated mice after 10 months appear to have the physical hallmarks of aging, such as hair loss and reduced body mass, early compared to CRE control mice (Yang et. al. 2023).

The haggard appearance of the ICE 10 month old mice confirmed the early aging effects of the epigenetic changes (Figure 2). At the molecular level, analysis of DNA methylation at genome sites associated with age showed that ICE cells were approximately 1.5 times “older” than the control cells. With this artificially increased age came physiological consequences. ICE mice showed diminished short-term memory retention compared to Cre-control mice, as assessed by fear conditioning tests, and the ICE mice performed half as well in a Barnes Maze test as control, indicating decreased long-term memory. Additionally, ICE mice had decreased muscle mass and grip strength after 16 months. The authors attributed the cause of this accelerated aging to increased “faithful DNA repair” from the induced DSB breaks in the ICE mice, meaning that there were not significant mutations in the repair of DSBs.(Yang et al., 2023). During DSB repair, chromatin modifying factor proteins activate and move within a cell in a process known as “relocalization,” with repeated activation of this process known to cause epigenetic changes that silence genes normally expressed in young mice. Sinclair’s lab hypothesized that the relocalization of chromatin modifiers that occurs from repeated DSB repair associated with induced epigenetic changes lead to a gradual loss of cellular function associated with aging (Yang et al., 2023).

It may seem ironic that DNA strand break repair, a process meant to keep cells functioning when critical genes are damaged, is part of what ultimately causes the death of organisms. The fact that the mechanism implemented is epigenetic rather than genetic suggests that the effects of ageing may be reversible, like epigenetic mechanisms. In fact, Sinclair has shown that it is possible to partially undo the damaging effects of aging: after inducing OSK expression, which is a set of proteins known as “Yamanaka factors,” ICE mice exhibited some signs of rejuvenation in their eyes, kidneys, and muscles. Yamanaka factors like OSK are important in the fields of aging and regenerative medicine because they are keys to the synthesis of induced pluripotent stem cells, where somatic cells can become stem cells and potentially re-differentiate into other cell types (Takahashi and Yamanaka, 2006). The OSK treatment decreased the expression of age-associated markers in the kidney and muscle cells of the mice (Yang et al., 2023).

Sinclair’s experiments have shown the epigenome to be a key front in the investigation of aging, as the reversibility of changes to the epigenome can allow it to be a more accessible interface for scientists to interact with. The plasticity of the epigenome as demonstrated from the ability of Yamanaka factors to reverse the molecular indicators of aging mice show that there may be hope for science to bring this phenomenon to human epigenomes. Indeed, the news of reversing aging in mice made rounds in the media when Sinclair’s paper was published earlier this winter, and for good reason.

Works Cited

Al Aboud, N. M., Tupper, C., & Jialal, I. (2022). Genetics, Epigenetic Mechanism. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532999/

Bannister, A. J., & Kouzarides, T. (2011). Regulation of chromatin by histone modifications. Cell Research, 21(3), Article 3. https://doi.org/10.1038/cr.2011.22

BOGObiology (Director). (2017, October 11). Epigenetics: Nature vs. Nurture. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q8BMP6HDIco

CDC. (2022, August 15). What is Epigenetics? | CDC. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/genomics/disease/epigenetics.htm

David Sinclair | The Sinclair Lab. (n.d.-a). Retrieved March 5, 2023, from https://sinclair.hms.harvard.edu/people/david-sinclair

Fernandez, A., O’Leary, C., O’Byrne, K. J., Burgess, J., Richard, D. J., & Suraweera, A. (2021). Epigenetic Mechanisms in DNA Double Strand Break Repair: A Clinical Review. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences, 8, 685440. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmolb.2021.685440

Gilbert, S. F. (2000). Methylation Pattern and the Control of Transcription. Developmental Biology. 6th Edition. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK10038/

Hannum, G., Guinney, J., Zhao, L., Zhang, L., Hughes, G., Sadda, S., Klotzle, B., Bibikova, M., Fan, J.-B., Gao, Y., Deconde, R., Chen, M., Rajapakse, I., Friend, S., Ideker, T., & Zhang, K. (2013). Genome-wide Methylation Profiles Reveal Quantitative Views of Human Aging Rates. Molecular Cell, 49(2), 359–367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2012.10.016

Jin, B., Li, Y., & Robertson, K. D. (2011). DNA Methylation. Genes & Cancer, 2(6), 607–617. https://doi.org/10.1177/1947601910393957

Kulis, M., & Esteller, M. (2010). 2—DNA Methylation and Cancer. In Z. Herceg & T. Ushijima (Eds.), Advances in Genetics (Vol. 70, pp. 27–56). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-380866-0.60002-2

Molecules discovered that extend life in yeast, human cells. (n.d.). EurekAlert! Retrieved March 5, 2023, from https://www.eurekalert.org/news-releases/664233.

Moore, L. D., Le, T., & Fan, G. (2013). DNA Methylation and Its Basic Function. Neuropsychopharmacology, 38(1), 23–38. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2012.112

Offord, Catherine. Two research teams reverse signs of aging in mice. (n.d.). Retrieved March 14, 2023, from https://www.science.org/content/article/two-research-teams-reverse-signs-aging-mice.

Takahashi, K., & Yamanaka, S. (2006). Induction of Pluripotent Stem Cells from Mouse Embryonic and Adult Fibroblast Cultures by Defined Factors. Cell, 126(4), 663–676. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024

What is Epigenetics? The Answer to the Nature vs. Nurture Debate. (n.d.). Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University. Retrieved March 5, 2023, from https://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/what-is-epigenetics-and-how-does-it-relate-to-child-development/

Wu, H., & Sun, Y. E. (2009). Reversing DNA Methylation: New Insights from Neuronal Activity–Induced Gadd45b in Adult Neurogenesis. Science Signaling, 2(64), pe17–pe17. https://doi.org/10.1126/scisignal.264pe17

Wu, H., & Zhang, Y. (2014a). Reversing DNA Methylation: Mechanisms, Genomics, and Biological Functions. Cell, 156(0), 45–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.019

Yang, J.-H., Hayano, M., Griffin, P. T., Amorim, J. A., Bonkowski, M. S., Apostolides, J. K., Salfati, E. L., Blanchette, M., Munding, E. M., Bhakta, M., Chew, Y. C., Guo, W., Yang, X., Maybury-Lewis, S., Tian, X., Ross, J. M., Coppotelli, G., Meer, M. V., Rogers-Hammond, R., … Sinclair, D. A. (2023). Loss of epigenetic information as a cause of mammalian aging. Cell, 186(2), 305-326.e27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2022.12.027