AI for Language and Cultural Preservation

Abstract

Nearly half of the world’s languages face extinction, threatening irreplaceable knowledge and cultural connections. This paper examines how artificial intelligence can support endangered language documentation and revitalization when guided by community priorities. Through case studies, from Hawaiian speech recognition to Cherokee learning platforms, the paper identifies both opportunities (improved access, engaging tools, cross-distance connection) and challenges (privacy risks, cultural appropriation, misinformation, sustainability). The central argument: effective preservation requires community leadership, robust consent frameworks, and sustained support rather than commodified technological quick fixes. The paper concludes with principles for responsible AI use that strengthens living languages and their cultural contexts.

Introduction

Approximately 40% of the world’s 6,700 languages risk extinction as speaker populations decline (Jampel, 2025). This crisis extends beyond communication loss. Languages embody cultural identity, historical memory, and community bonds. When languages disappear, speakers lose direct access to ancestral knowledge, particularly where oral histories predominate. Research suggests linguistic heritage connection correlates with improved adolescent mental health outcomes and reduced rates of certain chronic conditions.

Artificial intelligence has emerged as one approach to preservation, offering unprecedented documentation scale and interactive learning platforms. However, concerns persist beyond environmental costs, to whether technology can authentically serve community needs.

This paper argues that while AI provides powerful tools for endangered language work through natural language processing and speech recognition, success depends on careful integration with Indigenous communities’ priorities, values, and active participation.

It first examines AI’s technical foundations, real-world applications and case studies, diverse stakeholder perspectives, and future promises and challenges facing the field.

Technical Foundations: How AI Works in Language Preservation

To understand how AI contributes to language preservation, it is helpful to see how Natural Language Processing provides the foundational methods for analyzing language, while modern language models apply these methods to learn from data and produce meaningful representations and outputs that support language preservation-focused tasks.

Natural Language Processing

Natural Language Processing (NLP) sits at the core of how AI is used to process and manipulate text. Two key areas inform language documentation: Computational Linguistics (developing tools and methods for analyzing language data) and Semantics (studying how meaning operates in language).

Semantics broadly concerns deriving meaning from language. It spans the linguistic side, where it handles lexical and grammatical meaning tied to computational linguistics, and the philosophical side, which examines distinctions between fact and fiction, emotional tone (e.g., positive, neutral, negative), and relationships between different corpora (Ali et al., 2025, p. 133).

Semantics can address challenges like word ambiguity: where lie could mean falsehood or resting horizontally. Computational Linguistics tools like Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) use contextual analysis to disambiguate such terms. Other common challenges include capturing idiomatic meanings in translation (Ali et al., 2025, p. 134).

Computational Linguistics began in the 1940s-50s, but recent advancements have driven major developments in NLP through Machine Learning and Deep Learning. Neural networks, which are data-processing structures inspired by the human brain, allow machines to learn from sample data to perform complex tasks by recognizing, classifying, and correlating patterns.

In more recent years, Generative AI has gained prominence. It relies on transformer architectures, a type of neural network that analyzes entire sequences simultaneously to determine which parts are most important, enabling effective learning from large datasets.

In short, NLP implementation involves preprocessing textual data through steps such as tokenization (breaking text into smaller units), stemming or lemmatization (reducing words to their root forms, e.g., talking → talk), and stop-word removal (eliminating common or low-value words like and, for, with). The processed data is then used to train models for specific tasks.

Common NLP applications relevant to language preservation include part-of-speech tagging, which labels words in a sentence based on their grammatical roles (e.g., nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs); word-sense disambiguation, which resolves multiple possible meanings of a word; speech recognition, which converts spoken language into text; machine translation, which enables translation between languages; sentiment analysis, which identifies emotional tone in text; and automatic resource mining, which involves the automated collection of linguistic resources (Amazon Web Services, n.d.).

Language Models

BERT, developed by Google, is trained mainly with masked language modeling, where it predicts missing words from surrounding context. The original BERT also included a next sentence prediction task to judge whether one sentence follows another, although many modern variants modify or omit this objective (BERT, n.d.). Multilingual BERT (MBERT) extends this ability to multiple languages (Ali et al., 2025, p. 136).

Building on these advances, Cherokee researchers are applying and extending NLP techniques to advance language preservation and revitalization. According to Dr. David Montgomery, a citizen of the Cherokee Nation, “It would be a great service to Cherokee language learners to have a translation tool as well as an ability to draft a translation of documents for first-language Cherokee speakers to edit as part of their translation tasks” (Zhang et al., 2022, p. 1535).

To realize this potential, the research effort focuses on adapting existing NLP frameworks and creating tools specifically suited to Cherokee. Effective data collection and processing depend on capabilities such as automatic language identification and multilingual embedding models. For example, aligning Cherokee and English texts requires projecting sentences from both languages into a common semantic space to evaluate their similarity. These are capabilities that most standard NLP tools don’t provide and must be custom-built for this context (Zhang et al., 2022, p. 1535).

Real-World Applications and Case Studies

Broadly speaking, researchers and developers are creating innovative AI solutions to support language preservation across communities.

For example, the First Languages A.I. Reality (FLAIR) Initiative develops adaptable AI tools for Indigenous language revitalization worldwide. Co-founder Michael Running Wolf (Northern Cheyenne Tribe) describes the project’s goal as increasing the number of active speakers through accessible technologies. One notable product, “Language in a Box,” is a portable, voice-based learning system that delivers customizable guided lessons for different languages (Jampel, 2025).

Indigenous scientists are also creating culturally grounded AI tools for youth engagement. Danielle Boyer developed Skobot, a talking robot designed to speak Indigenous languages (Smithsonian Magazine), while Jacqueline Brixey created Masheli, a chatbot that communicates in both English and Choctaw. Brixey notes that despite more than 220,000 enrolled Choctaw Nation members, fewer than 7,000 are fluent speakers today (Brixey, 2025)

Hawaiian Language Revitalization – ASR

A collaboration between The MITRE Corporation, University of Hawai‘i at Hilo, and University of Oxford explored Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR) for Hawaiian, a low-resource language. Using dozens of hours of labeled audio and millions of pages of digitized Hawaiian newspaper text, researchers fine-tuned models such as Whisper (large and large-v2), achieving a Word Error Rate (WER) of about 22% (Chaparala et al., 2024, p. 4). This is promising for research and assisted workflows, but it remains challenging for beginner and intermediate learners without human review.

The models struggled with key phonetic features, particularly the glottal stop (ʻokina ⟨ʻ⟩) and vowel length distinctions, due to their subtle acoustic properties. Occasionally, the model substituted spaces for glottal stops, potentially due to English linguistic patterns where glottal stops naturally occur before vowels that begin words. Hawaiian’s success with Whisper benefited from available training data, including 338 hours of Hawaiian and 1,381 hours of Māori, and its Latin-based alphabet. Other under-resourced languages lacking such advantages may face greater transcription challenges (Chaparala et al., 2024, p. 4).

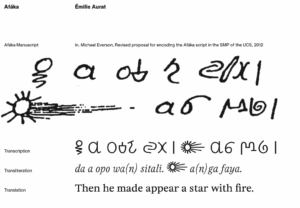

Missing Scripts Initiative – Input Methods

The Missing Scripts Initiative, led by ANRT (National School of Art and Design, France) in collaboration with UC Berkeley’s Script Encoding Initiative and the University of Applied Sciences, Mainz, addresses a major gap: nearly half of the world’s writing systems lack digital representation.

Launched in 2024 as part of the International Decade of Indigenous Languages, the initiative recognizes that beyond simply encoding these scripts into standard formats, there is the need to create functional input methods that allow users to type and interact with these writing systems. Developing these digital typefaces requires collaboration among linguists, developers, and native speakers. The initiative’s primary objectives involve encoding these scripts, a standardization process that assigns unique numerical identifiers to each character, and producing digital fonts. This work supports UNESCO’s global efforts to preserve and revitalize Indigenous linguistic heritage (UNESCO, n.d.).

Cherokee Case Study – Tokenization & Community-based Language Learning

Researchers at UNC Chapel Hill found that Cherokee’s strong morphological structure, where a single word can express an entire English sentence, poses unique NLP challenges. Character-level modeling using Latin script proved more effective than traditional word-level tokenization. Moreover, because Cherokee’s word order varies depending on discourse context, translating entire documents at once may be more effective than translating one sentence at a time (Zhang et al., 2022, p. 1535-1536).

Beyond technical modeling, researchers emphasized community-driven learning platforms that combine human input with AI. Inspired by systems like Wikipedia and Duolingo, these collaborative tools crowdsource content from speakers and learners. These platforms address two critical challenges simultaneously: the scarcity of training data for endangered languages and the resulting limitations in model performance. This approach transforms language learning from an individual task into a collective effort aimed at cultural preservation (Zhang et al., 2022, p. 1532).

Community Perspectives: Strengths and Concerns

A study by Akdeniz University researchers examined community perspectives on AI for language preservation, highlighting both benefits and challenges.

Strengths

Community members emphasized the transformative role of mobile apps in democratizing access: “Mobile apps have democratized access to our language, allowing learners from geographically dispersed areas to engage with it daily.” Interactive games and voice recognition tools make learning more engaging and accessible, while digital platforms foster connection and belonging among geographically dispersed speakers.

Translation tools and automated content generation have also proven valuable, with one linguist commenting that these technologies have been “game-changers in making our stories universally accessible.” Participants also underscored the value of cross-disciplinary collaboration, with one project manager noting that partnerships between tech developers and Indigenous communities have “opened new pathways for innovation.” AI’s adaptability was seen as another strength, allowing solutions to be customized for each language community (Soylu & Şahin, 2024. p. 15). For example, prioritizing translation tools over transcription systems depending on local needs.

Concerns

Participants also voiced serious concerns about ethics, privacy, and cultural sensitivity. One community leader stressed the importance of ensuring that “these technologies respect our cultural values and the integrity of our languages.” Limited internet infrastructure, funding instability, and intergenerational gaps remain ongoing barriers. As another participant observed, “Bridging the gap between our elders and technology is ongoing work.” Long-term sustainability depends on reliable funding and culturally informed consent practices (Soylu & Şahin, 2024. p. 15).

The Human and Cultural Dimensions

Focusing in on specific themes and perspectives, Indigenous innovators emphasize AI cannot replace human elders and tradition keepers. Technology should complement traditional practices like classes and intergenerational transmission. “Language is a living thing,” requiring living speakers, cultural context, and human relationships (Jampel, 2025).

Language preservation carries profound emotional and cultural significance. It is not merely the deployment of ‘fancy technology’ but usually a response to the deep wounds caused by historical oppression, including forced assimilation, the systematic suppression of Indigenous languages, and the displacement of communities from their ancestral lands (Brixey, 2025). For many, language revitalization is not just an educational effort but an act of cultural healing and the restoration of what was forcibly taken.

Critical Concerns and Emerging Risks

Beyond community-identified challenges, broader concerns about AI’s role in language preservation have emerged, particularly regarding quality control and misinformation. In December 2024, the Montreal Gazette reported the sale of AI-generated “how-to” books for endangered languages, including Abenaki, Mi’kmaq, Mohawk, and Omok (a Siberian language extinct since the 18th century). These books contained inaccurate translations and fabricated content, which Abenaki community members described as demeaning and harmful, undermining both learners’ efforts and trust in legitimate revitalization work (Jiang, 2025).

Many Indigenous communities also remain cautious about adopting AI. Jon Corbett, a Nehiyaw-Métis computational media artist and professor at Simon Fraser University, noted that some communities “don’t see the relevance to our culture, and they’re skeptical and wary of their contribution. Part of that is that for Indigenous people in North America, their language has been suppressed and their culture oppressed, so they’re weary of technology and what it can do” (Jiang, 2025). This caution reflects historical trauma and highlights critical questions about control, ownership, and ethical deployment of AI in cultural contexts.

Toward Ethical and Decolonized Approaches

Scholars emphasize decolonizing speech technology—respecting Indigenous knowledge systems rather than imposing Western frameworks. In 2019, Onowa McIvor and Jessica Ball, affiliated with the University of Victoria in Canada, underscored community-level initiatives supported by coherent policy and government backing (Soylu & Şahin, 2024. p. 13).

Before developing computational tools, speaker communities’ basic needs must be met: “respect, reciprocity, and understanding.” Researchers must avoid treating languages as commodities or prioritizing dataset size over community wellbeing. Common goals must be established before research begins. Only through such groundwork can AI technologies truly serve language revitalization rather than becoming another tool of extraction and exploitation (Zhang et al., 2022, p. 1531) .

These perspectives reveal that while technology offers promising pathways for language revitalization, success depends fundamentally on addressing both technical and sociocultural barriers through genuinely community-centered approaches that honor the living, relational nature of language itself.

Future Challenges and Considerations

The Low-Resource Language Challenge

A key obstacle in applying AI to endangered languages is the lack of large training datasets. High-resource languages like English and Spanish rely on millions of parallel sentence pairs for accurate translation (Jampel, 2025), but many endangered languages have limited or no written resources. Some lack a script entirely, requiring more intensive dataset curation and multimodal approaches.

To address this, Professor Jacqueline Brixey and Dr. Ron Artstein compiled a dataset combining audio, video, and text, with many texts translated into English, allowing models to leverage multiple modalities (Brixey, 2025). Similarly, Jared Coleman at Loyola Marymount University is developing translation tools for Owens Valley Paiute, a “no-resource” language with no public datasets. His system first teaches grammar and vocabulary to the model, then has it translate using this foundation, mimicking human strategies when working with limited data. Coleman emphasizes: “Our goal isn’t perfect translation but producing outputs that accurately convey the user’s intended meaning” (Jiang, 2025).

Capturing Linguistic and Cultural Features

Major models like ChatGPT perform poorly with Indigenous languages. Brixey notes: “ChatGPT could be good in Choctaw, but it’s currently ungrammatical; it shares misinformation about the tribe” (Jampel, 2025). Models fail to understand cultural nuance or privilege dominant culture perspectives, potentially mishandling sensitive information. These failures underscore the need for better security controls and validation mechanisms to mitigate the potential harm of linguistic misinformation.

Technical challenges extend to basic digitization processes as well. For example, most Cherokee textual materials exist as physical manuscripts or printed books, which are readable by humans but not machine-processable. This limits applications such as automated language-learning tools. Optical Character Recognition (OCR), using systems like Tesseract-OCR and Google Vision OCR, can convert these materials into machine-readable text with reasonable accuracy. However, OCR performance is highly sensitive to image quality. Texts with cluttered layouts or illustrations, common in children’s books, often yield lower recognition rates, posing ongoing challenges for digitization and digital preservation efforts (Zhang et al., 2022, p. 1536).

Ethical and Governance Issues

The exploitation of Indigenous languages has deep historical roots that continue to shape debates on AI development. In 1890, anthropologist Jesse Walter Fewkes recorded Passamaquoddy stories and songs, some sacred and meant to remain private, but the community was denied access for nearly a century, highlighting longstanding issues of linguistic sovereignty (Jampel, 2025).

More recently, in late 2024, the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe sued an educational company for exploiting Lakota recordings without consent, profiting from tribal knowledge, and demanding extra fees to restore access (Jampel, 2025).

In response, researchers like Brixey and Boyer implement protective measures, allowing participants to withdraw recordings and exclude their knowledge from AI development. These practices uphold data sovereignty, ensuring Indigenous communities retain control over their cultural knowledge and limiting commercialization. There is also a strong emphasis on keeping these technologies within Indigenous communities, preventing them from being commercialized or sold externally (Jampel, 2025).

As such, AI for language preservation requires clear policies for data governance and ethics. Some projects illustrate how AI can be ethically applied. New Zealand’s Te Hiku Media “Kōrero Māori” project uses AI for Māori language preservation under the Kaitiakitanga license, which forbids misuse of local data. CTO Keoni Mahelona emphasizes working with elders to record voices for transcription, demonstrating that AI tools can support Indigenous languages while respecting cultural values and community control (Jiang, 2025). Balancing technological openness with cultural sensitivity remains essential.

Resource and Infrastructure Needs

Beyond technical and ethical challenges, practical resource constraints significantly limit the scope and sustainability of language preservation initiatives. Securing funding for long-term projects remains one of the most persistent obstacles, as language revitalization requires sustained commitment over decades rather than short-term grant cycles. Training represents another critical need: communities require skilled teachers, technology experts, and materials developers who understand both the technical systems and the cultural context.

Infrastructure gaps pose fundamental barriers to participation. Many Indigenous communities lack reliable internet access and technology availability, limiting who can engage with digital language tools. Even when technologies are developed, communities need training to use and maintain AI tools independently, ensuring that these systems serve rather than create dependencies. Addressing these resource and infrastructure needs is essential for moving from pilot projects to sustainable, community-controlled language preservation ecosystems.

Conclusion

AI and NLP technologies hold significant promise for language preservation, addressing a critical need as many languages approach extinction due to declining numbers of speakers.

However, these technologies face inherent technical limitations. Low-resource languages often lack sufficient written materials or even a formal script, making model training difficult. LLMs trained primarily on English and other major languages struggle to capture the lexical, grammatical, and semantic nuances of endangered languages.

Equally important is the role of communities. Successful preservation depends on Indigenous leadership, ethical oversight, sustained collaboration, and adequate funding. AI should not be seen as a replacement for human knowledge but as one tool among many in a broader preservation toolkit.

Ultimately, digital preservation empowers communities to maintain and revitalize their linguistic heritage. Languages are living systems that thrive through active human relationships, and technology’s role is to support, not replace, these connections between people, language, and culture.

Bibliography

Ali, M., Bhatti, Z. I., & Abbas, T. (2025). Exploring the Linguistic Capabilities and Limitations of AI for Endangered Language preservation. Journal of Development and Social Sciences, 6(2), 132–140. https://doi.org/10.47205/jdss.2025(6-II)12

BERT. (n.d.). Retrieved November 6, 2025, from https://huggingface.co/docs/transformers/en/model_doc/bert

Brixey, J. (Lina). (2025, January 22). Using Artificial Intelligence to Preserve Indigenous Languages—Institute for Creative Technologies. https://ict.usc.edu/news/essays/using-artificial-intelligence-to-preserve-indigenous-languages/

Chaparala, K., Zarrella, G., Fischer, B. T., Kimura, L., & Jones, O. P. (2024). Mai Ho’omāuna i ka ’Ai: Language Models Improve Automatic Speech Recognition in Hawaiian (arXiv:2404.03073). arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2404.03073

Digital preservation of Indigenous languages: At the intersection of. (n.d.). Retrieved November 6, 2025, from https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/digital-preservation-indigenous-languages-intersection-technology-and-culture

Jampel, S. (2025, July 31). Can A.I. Help Revitalize Indigenous Languages? Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/can-ai-help-revitalize-indigenous-languages-180987060/

Jiang, M. (2025, February 22). Preserving the Past: AI in Indigenous Language Preservation. Viterbi Conversations in Ethics. https://vce.usc.edu/weekly-news-profile/preserving-the-past-ai-in-indigenous-language-preservation/

Soylu, D., & Şahin, A. (2024). The Role of AI in Supporting Indigenous Languages. AI and Tech in Behavioral and Social Sciences, 2(4), 11–18. https://doi.org/10.61838/kman.aitech.2.4.2

Students with Skobots on their shoulders stand next to Danielle Boyer. The STEAM Connection. (n.d.). [Graphic]. Retrieved November 6, 2025, from https://th-thumbnailer.cdn-si-edu.com/8iThtG8bZkWMxUq0goedXRXlzio=/fit-in/1072×0/filters:focal(616×411:617×412)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a5/f3/a5f3877c-f738-423d-bcff-8a44efcbe48f/danielle-boyer-and-student-wearing-skobots_web.jpg

The Missing Scripts. (n.d.). [Graphic]. Retrieved November 6, 2025, from https://sei.berkeley.edu/the-missing-scripts/

What is NLP? – Natural Language Processing Explained – AWS. (n.d.). Amazon Web Services, Inc. Retrieved November 6, 2025, from https://aws.amazon.com/what-is/nlp/

Zhang, S., Frey, B., & Bansal, M. (2022). How can NLP Help Revitalize Endangered Languages? A Case Study and Roadmap for the Cherokee Language. In S. Muresan, P. Nakov, & A. Villavicencio (Eds.), Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers) (pp. 1529–1541). Association for Computational Linguistics. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2022.acl-long.108