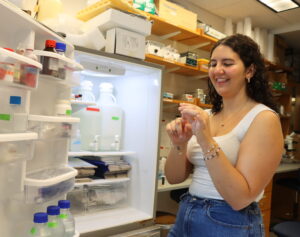

“I am delirious in lab. You have to be to have fun” – Yasemin Altug

When she was 12 years old, Yasemin cared little for popular book series like Percy Jackson or Harry Potter. Instead, she read Beyin Nasıl Çalışır? – How Does the Brain Work? in Turkish – before going to sleep. At that age, her mom said she was a “special child”. As the years passed, her interest in neuroscience only grew. Now, Yasemin is an undergraduate senior researcher in Bowdoin College’s Powell lab where she studies the lobster cardiac nervous system (hence the red lab coat).

On a late September morning, Yasemin invited me into the lab. As she gathered ice to numb the lobster, she explained that small fluctuations in temperature can disrupt crucial functions mediated by the lobster’s nervous system, like breathing and pumping blood. Whereas our warm-blooded bodies can regulate our body temperature, cold-blooded creatures, like lobsters, are at the whim of their environments.

In the Gulf of Maine, that environment is heating up as a result of global warming and shifting currents. To understand how the lobster’s cardiac nervous system responds, Yasemin investigates how, or even if a specific heart-modulating hormone is involved in warming compensation. To do so, she measures the lobster’s heartbeat at various temperatures in the presence and absence of the hormone. When cardiac neurons are active, they leave behind identifiable signatures in the heartbeat force signal on the cardiogram. Yasemin can use these signatures to derive whether the hormone is affecting activity in specific cardiac neurons, and if warming conditions change those hormone-neuron interactions. She can then use that information to construct a more complete picture of ocean warming effects on lobsters.

To conduct her experiments, Yasemin has to pay the cost of a living organism as she collects the lobster from its tank, numbs it, dissects it, and cannulates its heart. This meticulous work comes with feelings of discomfort and guilt. To overcome those feelings, she focuses on how her studies might help the lives of people living in Maine. In this state, a string of lobster-dependent communities lines the coast. Lobsters hold ecological, cultural, and economic value to these communities. After all, tourists do not come to Maine for its chicken sandwiches. Therefore, warming oceans pose a threat not only to Maine’s coastal ecosystem, but also its culture and to people’s livelihoods. The relevance of her research in all these contexts makes it worth the effort.

“I have to do what I have to do for the net positive outcomes of research. I think this is more important than my discomfort.”

“Being a good scientist is not about understanding the concepts with ease, it’s not about being perfect, it’s about being able to deal with mishaps… because scientists don’t care if you know how to hold a pipet, they care if you can learn how to hold a pipet.”