Many of us reflect on our childhoods as a time of blissful lack of social inhibition. As kids, we are often unaffected by the sense of embarrassment and self-consciousness which can hold us back as adults. This lack of social inhibition could explain why kids — even those as young as one year old — seem to have an inherent inclination to be helpful towards others (Plötner et al., 2015, p. 500). In fact, psychological forces which lead adults to resist offering their help can have a very different effect on kids. One such example is the bystander effect, which suggests that people are less likely to jump in and help someone in need when other onlookers are present. A previous study showed that the presence of bystanders can actually make children more likely to help (Plötner et al., 2015, p. 500). Researchers have identified three forces which may contribute to the bystander effect: social referencing, diffusion of responsibility, and shyness to act in front of others. Maria Plötner and colleagues recently conducted a study on the impact of diffusion of responsibility — the feeling of decreased sense of duty to help when more people are around — on children’s willingness to help an adult in need. The study calls into question our previous conceptions of kids as innately helpful, suggesting that children as young as five may be less likely to engage in helping behavior in the presence of other bystanders.

The researchers recruited sixty five-year-old participants to be assigned randomly to one of three conditions. In all conditions, the experimenter told the children that they were going to color a picture while she painted a cardboard wall. The test of helping came in after about thirty seconds, when the experimenter spilled her cup of dirty paint water all over her table. At regular intervals, she recited scripted dialogue (“oops,” “my cup has fallen over,” etc.) to let the children know she needed their help getting paper towels, which she had used to clean something up at the start of the experiment but were now out of her reach (Plötner et al., 2015, p. 501–502).

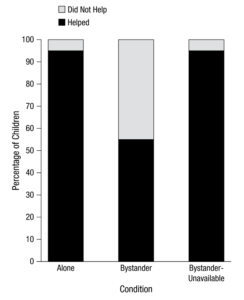

For each of the three conditions, the researchers recorded whether or not children helped the experimenter by bringing her a paper towel. The first was the “alone” condition, which was identical to the other two except for the fact that, as you might guess, there were no other children present. When they were alone, the subjects helped the experimenter about ninety five percent of the time (Plötner et al., 2015, p. 503). On the other hand, in the “bystander” condition, two “confederates” — other children in on the study — were present when the experimenter spilled her water and did nothing to help her. Here only about fifty five percent of subjects helped (Plötner et al., 2015, p. 503). Some might account for this difference using the concept of social referencing, our tendency to look to others when an emergency or accident takes place. When those around us seem not to notice or care about what’s happening, we use their behavior to inform our own. It’s easy to see how this could make the five-year-old subjects much less likely to bring the experimenter a paper towel, considering that the confederates had seen what happened but were completely indifferent to the experimenter’s distress.

But this study’s third condition, termed “bystander-unavailable,” put the social referencing explanation to the test. In this condition, while two other children were present, they were seated in such a way that they were physically unable to get up and help the experimenter (see Figure 1). Lo and behold, the children were much more likely to help when the other bystanders were “unavailable” than when they were also able to help. In fact, subjects helped just as often in the bystander-unavailable condition as when they were alone (Figure 2) (Plötner et al., 2015, p. 503). So social referencing really couldn’t explain why bystanders made the children less likely to help, since they were able to observe others’ indifference toward the experimenter in both bystander conditions. And if shyness to act in front of others had made the difference, we would have seen a low likelihood to help whenever others were present, not just in the regular bystander condition. So the researchers concluded that the diffusion of responsibility was the key force limiting these five-year-olds’ tendency to help while in the presence of others.

This study presents a novel discovery of the ability of even young children to dismiss their own sense of duty when they know they are not the only ones able to help. More broadly, it highlights the important role of taking responsibility for helping others in motivating us to actually step in. Meta-analyses of other studies on the subject have emphasized this, showing that people are less likely to take responsibility for helping when more bystanders are present and when “the need for help is ambiguous” (Plötner et al., 2015, p. 500). While it may not be possible to overcome the seemingly innate phenomenon of the bystander effect, being aware of it may allow us to take responsibility and offer our help in moments of need.

References

Plötner, M., Over, H., Carpenter, M., & Tomasello, M. (2015). Young Children Show the Bystander Effect in Helping Situations. Psychological Science, 26(4), 499-506. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797615569579