Are prescription antibiotics for acne worth it? Understanding the effects of long-term antibiotic usage on the gut microbiome offers new answers to this question.

Home to a diverse population of over 100 trillion microorganisms, the gut microbiome boasts significant influence over skin health through a complex, bidirectional relationship known as the gut-skin axis. When the gut microbiome is in equilibrium, or balance, skin health is enhanced through the promotion of skin barrier function and a decrease in inflammation. However, when the gut microbiome is in dysbiosis, or imbalance, skin disorders like acne vulgaris are more likely to occur (Munteanu et al., 2025).

Acne vulgaris is a chronic illness classified by inflammatory lesions, or areas with abnormal or damaged tissue. The most common treatment for moderate-to-severe acne involves prescription tetracycline-class antibiotics, such as minocycline or doxycycline. These antibiotics act broadly against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, which differ in their membrane and cell wall compositions. This broad-spectrum activity helps address acne by killing any bacteria that may be contributing to causative inflammation. However, this also results in disruptions to the microbial composition of the gut microbiome. To shed more light on this complicated relationship, Moura and colleagues sought to elucidate the impacts of long-term antibiotic usage on the gut microbiome in relation to the treatment of acne.

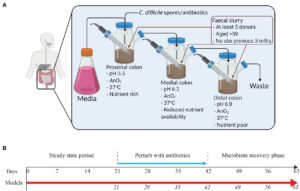

The experiment conducted by Moura et al. used in vitro gut models, consisting of live components outside of living organisms. Each of the three models was treated with a different tetracycline-class antibiotic before a recovery period to analyze the long-term consequences of each antibiotic treatment. The in vitro “Gut Models” comprised a triple-stage system with three vessels representing the proximal, medial, and distal colons. Within each model, in vivo physiological conditions – conditions that occur within biological organisms – including pH, oxygen content, temperature, and nutrient availability, were monitored. Reference Figure #1 for the experimental setup and timeline for each model.

Bacteria were introduced into all three vessels of the three models using fecal slurry (homogenized fecal matter) from five healthy adults who had not taken antibiotics in the past three months. Microbial populations had two weeks to reach a “steady state” before once daily treatment for three weeks with either 17 milligrams of sarecycline, 19.3 milligrams of minocycline, or 22 milligrams of doxycycline in models S, M, and D, respectively. Dosages were prepared based on reported antibiotic colonic values in humans.

Following antibiotic treatment, microbial populations in each model were monitored for three weeks in a microbiota recovery phase. This allowed the gut microbiome time to repopulate, if possible. Bacterial colonies were sampled daily from the models and subject to an enumeration protocol. In this procedure, they were grown on agar plates with different added components to distinguish microbial kinetics during antibiotic treatment and following withdrawal.

Following the conclusion of the microbial recovery phase, results pertaining to treatments of sarecycline, minocycline, and doxycycline, respectively, were achieved.

Single daily dosages of sarecycline resulted in a mean bioactive concentration of 15.9 mg/L across the three-week treatment regimen. However, levels of sarecycline became undetectable three days into the microbiota recovery phase. During treatment, microbial patterns indicated a significant decline in the Shannon diversity index, a baseline model for biodiversity. After week one, microbial diversity remained stable for the following two weeks of treatment. During the recovery phase, biodiversity increased, with many bacterial families returning to a healthy abundance.

Single daily dosages of minocycline resulted in a mean bioactive concentration of 27.4 mg/L. Significant decreases in microbial biodiversity were evident after three weeks of minocycline treatment. Dysbiosis was characterized primarily by the decrease of Bifidobacteriaceae and Lactobacillacea populations, coupled with an increase in Enterococcaceae and Enterobacteriaceae populations. During antibiotic withdrawal in the microbiota recovery phase, biodiversity was slow to recover, with several bacterial families failing to return to pre-treatment levels. Corynebacteriaceae, Planococcaceae, and Ruminococcaceae were nonexistent or marginally detectable at the end of the microbiota recovery phase.

Single daily dosages of doxycycline resulted in a mean bioactive concentration of 23.8 mg/L. Inconsistencies in microbe populations and decreased diversity were evident during treatment. Lower numbers of Lactobacillaceae and Bacteroidaceae especially characterized dysbiosis during treatment. Conversely, an increased abundance of Burkholderiaceae and Enterobacteriaceae was observed during treatment. Return of Lactobacillaceae, Enterobacteriaceae, and Burkholderiaceae populations to pre-treatment levels was not observed during the recovery phase.

Analyzing results from the experiment, it can be concluded that broad-spectrum antibiotics may significantly impact long-term composition, diversity, and equilibrium of the gut microbiome. Considering experimental data, sarecycline treatment results in the least disruption to the gut microbiome, in comparison to minocycline and doxycycline. Following sarecycline withdrawal, the profile of the gut microbiome returned to pre-sarecycline levels, in contrast to the significant long-term disruption following minocycline and doxycycline treatment (Moura et al., 2022). Further research, conducted by Elvers and colleagues, suggests that antibiotic-induced dysbiosis may last as long as several months or years, sometimes never returning to its original profile (Elvers et al., 2020).

Considering the importance of a healthy and diverse gut microbiome for skin health, the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics such as minocycline and doxycycline can pose a long-term risk of both gut and skin dysbiosis. Choosing antibiotic treatments such as sarecycline, which have more targeted bacterial effects, may prove beneficial for long-term microbial homeostasis. Moreover, abstaining from antibiotic treatment for acne vulgaris unless absolutely necessary may be more favorable in the consideration of long-term gut and skin health.

References:

Campos, M. (2023). Leaky gut: What is it, and what does it mean for you? Harvard Health Publishing. https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/leaky-gut-what-is-it-and-what-does-it-mean-for-you-2017092212451

Elvers, K. T., Wilson, V. J., Hammond, A., Duncan, L., Huntley, A. L., Hay, A. D., & Van Der Werf, E. T. (2020). Antibiotic-induced changes in the human gut microbiota for the most commonly prescribed antibiotics in primary care in the UK: a systematic review. BMJ Open, 10(9). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-035677.

Moura, I. B., Grada, A., Spittal, W., Clark, E., Ewin, D., Altringham, J., Fumero, E., Wilcox, M. H., & Buckley, A. M. (2022). Profiling the Effects of Systemic Antibiotics for Acne, Including the Narrow-Spectrum Antibiotic Sarecycline, on the Human Gut Microbiota. Frontiers in Microbiology, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.901911

Munteanu, C., Turti, S., & Marza, S. M. (2025). Unraveling the Gut–Skin Axis: The Role of Microbiota in Skin Health and Disease. Cosmetics, 12(4), 167. https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics12040167