Recent advances in machine-learning systems have led to both exciting and unnerving technologies—personal assistance bots, email spam filtering, and search engine algorithms are just a few omnipresent examples of technology made possible through these systems. Deepfakes (deep learning fakes), or, algorithm-generated synthetic media, constitute one example of a still-emerging and tremendously consequential development in machine-learning. WIRED recently called AI-generated text “the scariest deepfake of all”, turning heads to one of the most powerful text generators out there: artificial intelligence research lab OpenAI’s Generative Pre-Trained Transformer (GPT-3) language model.

Recent advances in machine-learning systems have led to both exciting and unnerving technologies—personal assistance bots, email spam filtering, and search engine algorithms are just a few omnipresent examples of technology made possible through these systems. Deepfakes (deep learning fakes), or, algorithm-generated synthetic media, constitute one example of a still-emerging and tremendously consequential development in machine-learning. WIRED recently called AI-generated text “the scariest deepfake of all”, turning heads to one of the most powerful text generators out there: artificial intelligence research lab OpenAI’s Generative Pre-Trained Transformer (GPT-3) language model.

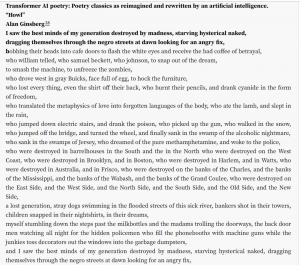

GPT-3 is an autoregressive language model that uses its deep-learning experience to produce human-like text. Put simply, GPT-3 is directed to study the statistical patterns in a dataset of about a trillion words collected from the web and digitized books. GPT-3 then uses its digest of that massive corpus to respond to text prompts by generating new text with similar statistical patterns, endowing it with the ability to compose news articles, satire, and even poetry.

GPT-3’s creators designed the AI to learn language patterns and immediately saw GPT-3 scoring exceptionally well on reading-comprehension tests. But when OpenAI researchers configured the system to generate strikingly human-like text, they began to imagine how these generative capabilities could be used for harmful purposes. Previously, OpenAI had often released full code with its publications on new models. This time, GPT-3s creators decided to hide its underlying code from the public, not wanting to disseminate the full model or the millions of web pages used to train the system. In OpenAI’s research paper on GPT-3, authors note that “any socially harmful activity that relies on generating text could be augmented by powerful language models,” and “the misuse potential of language models increases as the quality of text synthesis improves.”

Just like humans are prone to internalizing the belief systems “fed” to us, machine-learning systems mimic what’s in their training data. In GPT-3’s case, biases present in the vast training corpus of Internet text led the AI to generate stereotyped and prejudiced content. Preliminary testing at OpenAI has shown that GPT-3-generated content reflects gendered stereotypes and reproduces racial and religious biases. Because of already fragmented trust and pervasive polarization online, Internet users find it increasingly difficult to trust online content. GPT-3-generated text online would require us to be even more critical consumers of online content. The ability for GPT-3 to mirror societal biases and prejudices in its generated text means that GPT-3 online might only give more voice to our darkest emotional, civic, and social tendencies.

Because GPT-3’s underlying code remains in the hands of OpenAI and its API (the interface where users can partially work with and test out GPT-3) is not freely accessible to the public, many concerns over its implications steer our focus towards a possible future where its synthetic text becomes ubiquitous online. Due to GPT-3’s frighteningly successful “conception” of natural language as well as creative capabilities and bias-susceptible processes, many are worried that a GPT-3-populated Internet could do a lot of harm to our information ecosystem. However, GPT-3 exhibits powerful affordances as well as limitations, and experts are asking us not to project too many fears about human-level AI onto GPT-3 just yet.

GPT-3: Online Journalist

Fundamentally, concerns about GPT-3-generated text online come from an awareness of just how different a threat synthetic text poses versus other forms of synthetic media. In a recent article, WIRED contributor Renee DiResta writes that, throughout the development of photoshop and other image-editing CGI tools, we learned to develop a healthy skepticism, though without fully disbelieving such photos, because “we understand that each picture is rooted in reality.” She points out that generated media, such as deepfaked video or GPT-3 output, is different because there is no unaltered original, and we will have to adjust to a new level of unreality. In addition, synthetic text “will be easy to generate in high volume, and with fewer tells to enable detection.” Right now, it is possible to detect repetitive or recycled comments that use the same snippets of text to flood a comment section or persuade audiences. However, if such comments had been generated independently by an AI, DiResta notes, these manipulation campaigns would have been much harder to detect:

“Undetectable textfakes—masked as regular chatter on Twitter, Facebook, Reddit, and the like—have the potential to be far more subtle, far more prevalent, and far more sinister … The ability to manufacture a majority opinion, or create a fake commenter arms race—with minimal potential for detection—would enable sophisticated, extensive influence campaigns.” – Renee DiResta, WIRED

In their paper “Language Models are Few-Shot Learners,” GPT-3’s developers discuss the potential for misuse and threat actors—those seeking to use GPT-3 for malicious or harmful purposes. The paper states that threat actors can be organized by skill and resource levels, “ranging from low or moderately skilled and resourced actors who may be able to build a malicious product to … highly skilled and well resourced (e.g. state-sponsored) groups with long-term agendas.” Interestingly, OpenAI researchers write that threat actor agendas are “influenced by economic factors like scalability and ease of deployment” and that ease of use is another significant incentive for malicious use of AI. It seems that the very principles that guide the development of many emerging AI models like GPT-3—scalability, accessibility, and stable infrastructure—could also be what position these models as perfect options for threat actors seeking to undermine personal and collective agency online.

Staying with the projected scenario of GPT-3-text becoming widespread online, it is useful to consider the already algorithmic nature of our interactions online. In her article, DiResta writes about the Internet that “algorithmically generated content receives algorithmically generated responses, which feeds into algorithmically mediated curation systems that surface information based on engagement.” Introducing an AI “voice” into this environment could make our online interactions even less human. One example of possible algorithmic accomplices of GPT-3 are Google Autocomplete algorithms which internalize queries and often reflect “-ism” statements and biases while processing suggestions based on common searches. The presence of AI-generated texts could populate Google algorithms with even more problematic content and continue to narrow our ability to have control over how we acquire neutral, unbiased knowledge.

An Emotional Problem

Talk of GPT-3 passing The Turing Test reflects many concerns about creating increasingly powerful AI. GPT-3 seems to hint at the possibility of a future where AI is able to replicate those attributes we might hope are exclusively human—traits like creativity, ingenuity, and, of course, understanding language. As Microsoft AI Blog contributor Jennifer Langston writes in a recent post, “designing AI models that one day understand the world more like people starts with language, a critical component to understanding human intent.”

Of course, as a machine-learning model, GPT-3 relies on a neural network (inspired by neural pathways in the human brain) that can process language. Importantly, GPT-3 represents a massive acceleration in scale and computing power (rather than novel ML techniques), which give it the ability to exhibit something eerily close to human intelligence. A recent Vox article on the subject asks the question, “is human-level intelligence something that will require a fundamentally new approach, or is it something that emerges of its own accord as we pump more and more computing power into simple machine learning models?” For some, the idea that the only thing distinguishing human intelligence from our algorithms is our relative “computing power” is more than a little uncomfortable.

As mentioned earlier, GPT-3 has been able to exhibit creative and artistic qualities, generating a trove of literary content including poetry and satire. The attributes we’ve long understood to be distinctly human are now proving to be replicable by AI, raising new anxieties about humanity, identity, and the future.

GPT-3’s Limitations

While GPT-3 can generate impressively human-like text, most researchers maintain that this text is often “unmoored from reality,” and, even with GPT-3, we are still far from reaching artificial general intelligence. In a recent MIT Technology Review article, author Will Douglas Heaven points out that GPT-3 often returns contradictions or nonsense because its process is not guided by any true understanding of reality. Ultimately, researchers believe that GPT-3’s human-like output and versatility are the results of excellent engineering, not genuine intelligence. GPT-3 uses many of its parameters to memorize Internet text that doesn’t generalize easily, and essentially parrots back “some well-known facts, some half-truths, and some straight lies, strung together in what first looks like a smooth narrative,” according to Douglas. As it stands today, GPT-3 is just an early glimpse of AI’s world-altering potential, and remains a narrowly intelligent tool made by humans and reflecting our conceptions of the world.

A final point of optimism is that the field around ethical AI is ever-expanding, and developers at OpenAI are looking into the possibility of automatic discriminators that may have greater success than human evaluators at detecting AI model-generated text. In their research paper, developers wrote that “automatic detection of these models may be a promising area of future research.” Improving our ability to detect AI-generated text might be one way to regain agency in a possible future with bias-reproducing AI “journalists” or undetectable deepfaked text spreading misinformation online.

Ultimately, GPT-3 suggests that language is more predictable than many people assume, and challenges common assumptions about what makes humans unique. Plus, exactly what’s going on inside GPT-3 isn’t entirely clear, challenging us to continue to think about the AI “black box” problem and methods to figure out just how GPT-3 reiterates natural language after digesting millions of snippets of Internet text. However, perhaps GPT-3 gives us an opportunity to decide for ourselves whether even the most powerful of future text generators could undermine the distinctly human conception of the world and of poetry, language, and conversation. A tweet Douglas quotes in his article from user @mark_riedl provides one possible way to frame both our worries and hopes about tech like GPT-3: “Remember…the Turing Test is not for AI to pass, but for humans to fail.”