Watch a skilled rider enter a berm: they arrive tall, compress as the turn loads up, and rise on exit – no pedaling, yet they launch out faster. This isn’t magic; it’s timing that lets the ground do positive work on you. This reciprocal motion between the bike and the rider is called pumping, evident in three places: rollers, banked corners (berms), and jumps. This article focuses on the physics in berms and a recent model by Golembiewski and colleagues that computes an optimal pumping rhythm through corners. We finish with brief notes on extending the same logic to rollers and jumps.

The Basic Physics in a Berm

The ground must push hard on the bike to bend its path towards the center. That “heaviness” is the normal load N. A compact way to sketch the load you feel (or the “heaviness”) is:

![]()

The first term is gravity on a bank with tilt β , the second term is the centripetal demand of the turn (speed v, radius R), and the third term is what you add by moving your body normal to the surface (a rider)a: positive when you compress, negative when you unweight). Even if the radius R stays roughly constant through the main arc, N ramps up when you go from straight to arc (entry) and drops when you go from arc back to straight (exit). Those ramps are the windows that matter, when a sliver of the ground’s reaction force points forward along the bikes path (T). The instantaneous power is roughly P=Tv. You use this to gain speed.

The bike has two wheels, splitting the pumping motion into two time frames: a short bar press as the front hits the entry ramp, then a short pedal press as the rear reaches it. Those two brief pulses create two small forward pushes per berm. Note that this isn’t conservation of angular momentum (mvr) because the ground is doing external work but applying compressive forces at the right time.

Why this matters. This turns “pump the berm” from a vibe into a repeatable rule you can coach, measure, and design for: press twice in the entry window, glide out, and you bank real, compounding speed—no pedaling required.

Inside the Research: A Two-Mass Model on a Banked Ribbon

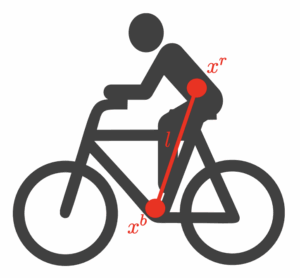

The paper starts with a cartoon model where the bike and the rider are represented by two points—centers of mass xb and xr — joined by a massless link of length l(t)

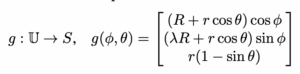

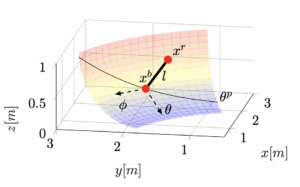

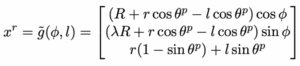

To give these points a world to live in, they build a 3D banked surface, called S, using a set of parametric equations:

Think of g as a recipe that turns the pair “where you are around the track (Φ)” and “where you are across the bank (Θ)” into a 3-D position. Rather than let the bike wander anywhere on S, the authors choose a riding line by prescribing as a function of Φ.

![]()

Subsequently, the author derives a position equation for the bike–rider system that depends only on Φ — the progress angle around the banked turn—under the riding line assumption that the rider holds an inner line on the straights and shifts toward the outer (higher) line near the apex.

To simplify the problem, the author also introduces an upright constraint (Fig. 4): this means the imaginary line between the bike and the rider is always perpendicular to the track surface. The movement of the rider will only be orthogonally, no fore–aft lean—so l(t) is exactly “how much you squat or extend” relative to the bank. Under that constraint, an explicit expression for the rider position (g̃) is derived.

This equation takes Φ — the progress angle around the banked turn, and l (the distance between the bike’s COM and the rider’s COM) as input, and outputs a point in 3D space.

Setting up an Equation of Motion

The authors model the bike–rider system with positions that vary over time. The bike position is xb(t) and the rider position is xr(t). Velocity is the time derivative of position (how fast the points move), and acceleration is the time derivative of velocity. A single “squat/extend” degree of freedom along the surface normal is captured by the body–bike separation l(t). In everyday terms, l̇ is how quickly you are moving up or down, and l̈ is how hard you accelerate that motion. This variable l̈(t) is the core of the study — it becomes the control input in the simulation. From the position formulas, the paper computes the speeds (kinetic energy)

and heights (potential energy) of both masses:

- Kinetic energy K = (bike term) + (rider term)

- Potential energy U = (gravity acting on each mass via its z-height)

Rather than listing every individual force, they use the standard energy approach to produce a single, compact equation that governs motion along the track. Written the way it appears in the paper, it’s an implicit ordinary differential equation (ODE) in the along-track angle φ(t) that also depends on your body motion l(t):

The terms mean:

- M(φ, l) φ̈ — the effective inertia for turning the system around the track.

- F(φ, l) φ̇2 — curvature/banking effects that grow with speed.

- Q(φ, l, l̇) φ̇ — coupling between your height change and along-track motion.

- P(φ, l, l̇, l̈) — the part driven by your deliberate squat/extend acceleration (l̈), i.e., the “pump.”

Intuition: When you accelerate your body normal to the surface while the berm sets the contact frame, the last term acts like a small forward push in the along-track equation. That is the mechanism the model quantifies.

Setting Up an Optimal Control Problem

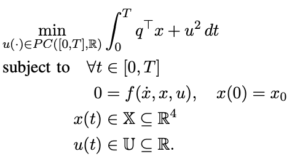

The paper asks a simple question: If you’re not allowed to pedal, how should you squat and extend to get through a banked turn the fastest? To answer it, they turn riding into a decision-making problem a computer can solve. This is called an optimal control problem.

State: Within the integral, x(t) is the state vector—it stores four numbers at every instant:

- Where you are around the corner (an angle): φ(t).

- How fast you’re sweeping around (angular rate; higher rate = higher speed): φ̇(t).

- How tall you are above the bike along the bank’s normal (body–bike separation): l(t).

- How quickly that height is changing (going up or down): l̇(t).

The researchers bundle these into a compact vector the computer updates over time, simulating the rider’s progress around the track:

![]()

Reward and punishment inside the integral: The cost being minimized adds a reward for making progress/speed and a penalty for harsh pumping:

- qT x(t) (Fig 5) is a linear reward/penalty on the state. In the paper, q = [ -65, -65, 0, 0 ]T. Because we minimize J, those negative weights reward larger φ (angle covered) and φ̇ (speed). In short: the optimizer prefers going farther and faster.

- u(t)2 penalizes violent pumping. Here u(t) = l̈(t) is the rider’s normal acceleration (how hard you compress or unweight). Sudden, large inputs make u2 jump, increasing the cost, so the optimizer favors smooth, well-timed pulses over thrashing.

Units intuition: the integrand is “cost per second.” Integrating over dt gives a total cost. Lower J means you went farther/faster while using less harsh acceleration.

Control (what you choose): Your single decision signal is how hard you accelerate your body up or down relative to the bike, along the bank’s normal direction—the essence of pumping:

- Positive control: compress (drive yourself down)

- Negative control: unweight (pop up)

They call this input u(t) = l̈(t)

The notation u(⋅) ∈ PC ([0,T], ℝ) (Fig 5) means the control is piecewise-continuous over the time window — mostly smooth with at most a few kinks.

Dynamics constraint (obeying physics): The model provides an equation tying together how the state changes when you pick a control, with a specified starting condition x(0)=x0:

![]() The equation basically means: given the track shape and gravity, if you push this hard right now, this rule predicts how your position, speed, and body height will evolve next. The solver enforces this rule at every tiny time step so it never “cheats.”

The equation basically means: given the track shape and gravity, if you push this hard right now, this rule predicts how your position, speed, and body height will evolve next. The solver enforces this rule at every tiny time step so it never “cheats.”

Setting Realistic Constraints

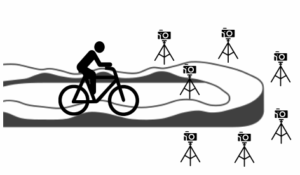

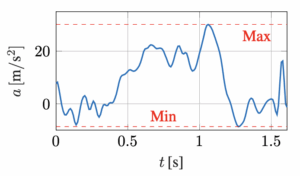

The researchers then determine the realistic bounds for length between the bike and rider and acceleration between the bike and rider by doing a motion capture of a real setup.

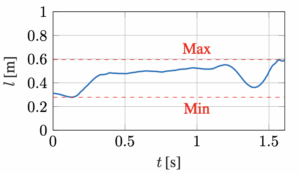

They use motion trackers to track 46 markers at 100 Hz and infer rider CoM and bike reference points to measure what a human can actually do. The result were the graphs below:

We can see the graph roughly mirrors the motion you feel in real life:

- Riders enter the berm pushing the bike down and extending length

- Riders maintain pressure throughout the berm and compresses near the end

- When riders exit the berm they push the bike down again and re-extend.

In this real-world experiment, researchers observed the range of body-bike length to be(0.27803m ≤ l(t) ≤ 0.59559 m) and body-bike acceleration (pumping) to be (-8.6648 m/s2 ≤ l̈(t) ≤ 30.1478 m/s2)

The researchers then substituted these bounds into their optimal control problem to determine the optimal pumping technique mathematically.

What the Model Predicts (and how it matches good riding)

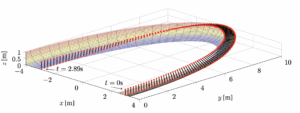

The researchers solved the optimal-control problem for a 5-second ride segment that includes two steep corners and two short straights. They start the rider in a neutral body position, traveling at an angular speed of φ̇ = π/3 rad/s (about 9.43 m/s bike speed),

entering at the beginning section between two opposing corners. They then plug the physical parameters into the dynamics (equation of motion):

| mb | mr | ggrav | R | r | λ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 kg | 80 kg | 9.8067 m/s2 | 3 m | 1 m | 3 |

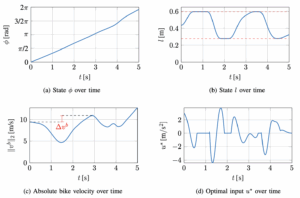

The track constants R, r, and λ determine the sharpness and banking of the corner (here R = 3 m, r = 1 m, λ = 3). Finally, using MATLAB (via CasADi) and IPOPT the researchers solve the optimal-control problem, successfully simulating a complete cycle through the track, producing the graphs below:

What the optimal solution does:

- Kinematics (Fig. 10a):ϕ(T) ends close to 2π — a full pass through the track section including both steep curves.

- Pose evolution (Fig. 10b):The optimal profile drives the body high at entry (near lmax), then compresses toward lmin across each corner, and re-extends later. In short: enter tall, compress through the berm, then re-extend for each berm. We can also see this visualized in Fig 3

- Speed gain (Fig. 10c):Remarkably, between t = 0 and t ≈ 2.8 s (the first berm), the bike speed increases by vb ≈ 1.49 m/s — generated without pedaling, purely by the reciprocal mass motion (squat/extend).

- Control signal (Fig. 10d):The input u*(t) = l̈(t) shows short downward-acceleration bursts (negative then positive spikes) clustered in each corner. These spikes are the timed “pump” impulses that increase normal load precisely when the track’s orientation gives a small forward component — at corner entry and exit — producing useful forward work.

They ran a comparison without pumping (set u(t) = 0, but tested several starting heights l(0)). The fastest no-input case took 6.13 s to reach the same terminal angle φ(T). With the optimal pumping u*(t), the time dropped to 5.00 s. That’s a time saving of Δt = 1.13 s — about 18.43% faster for the same path segment.

Bottom line

Within the paper’s simplified two-mass, upright model (with experiment-derived bounds), pumping through a berm means spending your limited normal-acceleration budget inside the corner (to harvest speed) and avoiding payback at the exit. The solver’s best answer matches what skilled riders do: enter tall, compress through the berm, re-extend later. The numbers quantify the payoff: roughly ≈ 1.5 m/s speed gain per corner and ≈ 18% reduction in lap time for the segment.

From Model to Trail: a Real-World Translation in Riding Technique

The paper’s takeaway is: spend your limited “normal-acceleration budget” inside the corner and don’t pay it back on exit. In practice, that means arrive tall, compress through the corner, and re-extend later (ideally once you’re back on a straight).

What the model doesn’t capture (and how real riders adapt) is:

- Only normal motion. The paper restricts the rider to move orthogonal to the track’s surface (no fore–aft pump). On dirt, riders can pump slightly forward/back as well. That can shift the pattern earlier, often giving a high → low → high within a single corner, instead of the model’s high → low (then high on the straight).

- One fixed line. The solver rides a prescribed line (inner on straights, drifting outward at apex). Outside the lab you can pick lines that change banking and gravity use:

- High → low line: drop from high entry to lower apex/exit to cash in gravitational energy while you compress.

- Low → high line: for traction or setup, at the cost of more input work.

- Two contacts, richer phasing. With front and rear wheels you get two timed opportunities per corner (bar press as the front enters the load ramp, pedal press as the rear reaches it). Skilled riders also unweight the front earlier to keep exit smooth.

Beyond Berms: Brief Notes on Rollers and Jumps

Rollers (smooth waving undulations): You speed up by placing two brief load pulses around each crest — bar press as the front rolls over the crest, pedal press as the rear follows — then staying light on the upslope so you don’t give the energy back. These two pulses creates a small forward push each. Add them up, subtract gravity and drag, and you get your acceleration

- Front wheel at crest (arms compact, legs half-extended). You’re coiling up at the exact moment curvature flips.

- Front on downside; rear crosses crest (arm push grows to full extension; legs fully compressed). Two quick injections: a bar press as the front tips over (raising front normal load just as the ground points forward), then a pedal press as the rear crests. Each creates a small forward contact component

- Front in ravine; rear on downside (arms finish extension, legs extend down the back face). Keep pedal pressure while the rear is still on the back face. begin to unweight the bars as the front meets the upslope to avoid negative work.

- Front on upslope; rear in ravine (legs reach full extension; arms half-compressed; front unweighted). Now the ground would slow you (upslope). You keep the front light and use the up-kick to pop your mass upward—maintaining speed while the bike climbs under you.

Jumps: Preload on the run-up, then choose: extend on the lip at the point of maximum normal force where m · v2 · κ is maximum (you can look at my personal research if interested) to trade speed for height or stay light to preserve forward speed. The same “press-when-helpful, light-when-hurtful” rule applies, just with a vertical-energy trade at takeoff.

Conclusion

Pumping is a control problem you solve with your body: press exactly while the turn makes you heavy, and rise while it makes you light. The research formalizes this with a minimal two-mass model and an optimizer that times a compress–extend input to harvest the berm’s geometry—a clean physics story for the “free speed” riders feel in corners.

Bibliography

Velosolutions Global. (2024, March 6). 2024 qualifier events announced for UCI Pump Track World Championships. Pinkbike. https://www.pinkbike.com/news/2024-qualifier-events-announced-for-uci-pump-track-world-championships.html

Golembiewski, J., Schmidt, M., Terschluse, B., Jaitner, T., Liebig, T., & Faulwasser, T. (2023). The dynamics of a bicycle on a pump track—First results on modeling and optimal control (arXiv Preprint No. 2311.07251). arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2311.07251