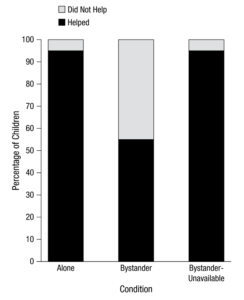

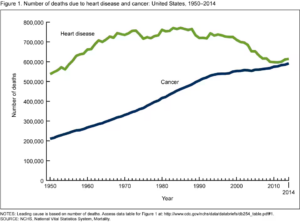

Right now, cancer is the second most common cause of death in the world, and it’s set to become the leading cause within the next several decades (Drexler) (Figure 1). Unlike many other diseases that have plagued humans throughout our history, even revolutionary advancements in medicine have not been able to fully prevent or cure it. To understand why, it’s important to recognize that cancer comes not from the outside, but from within ourselves, when our own cells begin to divide uncontrollably and spread throughout our bodies. Because cancer arises in our bodies, we can’t treat it using antibiotics or vaccines that target a particular pathogen. However, a 2023 study has proposed a new vaccine treatment that fights pancreatic cancer (which has a five-year survival rate of only 12%) using our own immune system.

To understand this discovery, it’s important to learn a little about how the immune system works. One important component of our body’s defense system are our T cells, which fight invaders by identifying and killing body cells infected with pathogens such as viruses. A T cell only knows what to attack after it’s activated by a foreign particle called an antigen. Antigens are often tiny pieces of invading viruses or bacteria, like “keys” which unlock a T cell immune response. Now, what does all this have to do with cancer? The idea behind this proposed treatment is to use neoantigens (a type of antigen) to help the body recognize cancer cells. Neoantigens are mutant proteins which only form on tumor cells, so helping T cells recognize them could help the body learn to attack cancerous cells.

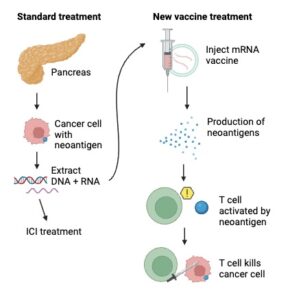

This study’s major discovery was a new way to prompt the immune system to recognize neoantigens. The researchers took genetic material (such as DNA and RNA) from the surgically removed tumors of sixteen people with pancreatic cancer. Then they gave each patient a kind of treatment called an immune-checkpoint inhibitor (ICI). Immune checkpoints are proteins on the surfaces of healthy cells which usually tell our T cells not to attack them. The problem is that sometimes, immune checkpoints on cancerous cells prevent T cells from attacking them too. ICIs can treat some kinds of cancers by blocking these interactions between T cells and cancerous cells, allowing T cells to kill them, but they often do not work well on pancreatic cancer. To solve this problem, the researchers used the genetic information collected from the tumors to create a personalized vaccine containing mRNA (a type of RNA) that codes for the exact neoantigen formed on an individual’s cancer cells. After receiving this vaccine, a person’s cells would be able to use the mRNA to produce this neoantigen in abundance. Then, their T cells could theoretically recognize it, become activated, and know to go after the cancer cells with the neoantigen on their surfaces (Figure 2). To maximize the chances of triggering this T cell response, the vaccines included mRNA coding for as many as twenty neoantigens.

Now for the big question: did it work? Well, cancer unfortunately came back an average of 13.4 months after treatment for half of the study’s participants. The other eight, however, all had T cells which recognized the artificial neoantigens in their bodies after vaccine treatment and also remained cancer-free after ~18 months (Huff & Zaidi, 2023). This vaccine is clearly not perfect, and future research is still needed to understand why half the patients’ immune systems did not respond to the treatment. However, it is still an incredible breakthrough that could shift the direction of cancer treatment. A clinical trial, the second phase of this study, is already well underway and includes over 250 patients (Stallard, 2024). Given the small sample size of this first study, the new clinical trial will help clarify how effective this vaccine treatment really is. Immunotherapy is emerging as a leading factor in the fight against cancer, and this study gives reason to believe that new treatment possibilities could be on the horizon for cancer patients, even those with aggressive tumors.

References

Drexler, M. (n.d.). The Cancer Miracle Isn’t a Cure. It’s Prevention. Harvard Public Health. https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/magazine/magazine_article/the-cancer-miracle-isnt-a-cure-its-prevention/.

Heron, M. & Anderson, R.N. (2016). Changes in the leading cause of death: Recent patterns in heart disease and cancer mortality. CDC: NCHS data brief, 254. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db254.htm.

Huff, A.L. & Zaidi, N. (2023, May 10). Vaccine boosts T cells that target pancreatic tumours. Nature. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-023-01526-8.

Rojas, L.A., Sethna, Z., Soares, K.C. et al. (2023). Personalized RNA neoantigen vaccines stimulate T cells in pancreatic cancer. Nature 618, 144–150. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06063-y.

Stallard, J. (2024, April 7). Investigational mRNA Vaccine Induced Persistent Immune Response in Phase 1 Trial of Patients With Pancreatic Cancer. Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. https://www.mskcc.org/news/can-mrna-vaccines-fight-pancreatic-cancer-msk-clinical-researchers-are-trying-find-out.