Dravet Syndrome (DS) is a form of pediatric epilepsy that produces prolonged seizures that cannot be prevented or stopped by available medications (Dravet Syndrome Foundation 2025). These seizures cause a wide range of severe health effects, ranging from cognitive impairment to infection and premature death (Dravet Syndrome Foundation 2025). Dravet syndrome is a disease that typically begins between 2 and 15 months of age and it affects 1:15,700 infants born (Dravet Syndrome Foundation 2025). While rare, this disease has a high mortality rate, with 15-20% of patients passing due to Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy (SUDEP) (Dravet Syndrome Foundation 2025).

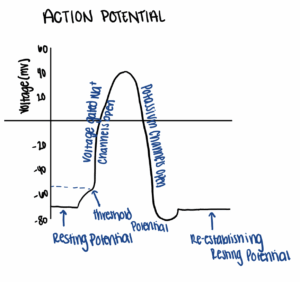

On the molecular level, DS is caused by a mutation in the SCN1A gene, which encodes a voltage gated sodium channel (Chow et al. 2019). This channel plays an important role in generating action potentials, which are the observable changes in cell voltage that conduct signals between nerves (Fig. 1). These electrical signals are transmitted by the movement of ions into and out of nerve cells, a transition that changes the charge of the cells. Typically, nerve cells have a resting potential of -70mV. When nerve cells reach the threshold potential, typically by allowing a small number of cations into the cell, the voltage gated sodium channels open, and a large number Na+ ions move into the cell, raising the voltage near +40mV. Once this new threshold is reached, the voltage gated sodium channels close and other channels open, allowing potassium ions to leave the cell. This removal of potassium from the cells drives the voltage back to a negative value. This process is vital to the correct transmission of electrical signals throughout the body to drive movement.

The mutation in the SCN1A gene alters the specific voltage-gated sodium channel 1.1 (Chow et al. 2019). Voltage-gated sodium channels are built from specifically folded proteins. In a normally functioning channel, there are two types of subunits: 1-2 β subunits and an ɑ subunit consisting of 4 distinct domains, or regions of the subunit (Chow et al. 2019). Each domain includes a voltage-sensing region, which detects alterations in cell voltage in order to signal for channel opening (Chow et al. 2019). A pore region is also present, which helps control the channel’s permeability (Chow et al. 2019). When SCN1A is mutated, several alterations to function can occur, including increased channel opening or channel mutations that prevent the influx of ions (Escayg and Goldin 2010). Unfortunately, even if only one copy of this gene is mutated, the functional copy is unable to overcome the deficit caused by the mutated gene, a principle known as haploinsufficiency.

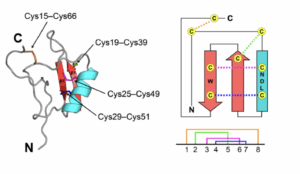

Thus, new approaches are needed to control when this dysfunctional channel opens and closes. Venom peptides are a rich source of what are known as channel modulators (Chow et al. 2019). These short molecules, formed from the same molecular building blocks as larger proteins, can assume unique shapes. These folded conformations are stabilized by the presence of numerous cysteine residues, which can form strong disulfide bridges to “lock” a peptide in place. The CSɑβ fold describes one such disulfide bridge which forms between the beta sheets and alpha helix in the protein structure (Fig. 2). Venom peptides containing these folds can act as both alpha and beta toxins, with alpha toxins causing inhibition of channel inactivation and beta toxins causing direct activation. Chow et al. (2019) investigated two of these dual modulatory venom peptides, Hj1a and Hj2a, both found in scorpion venom.

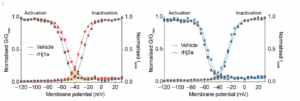

The researchers studied the activation and inactivation of both of the venom peptides (Fig. 3). For Hj1a, the activation threshold increases, making activation harder, and the inactivation threshold decreases, also making inactivation easier (Chow et al. 2019). This change limits the range of functioning for the channels and thus increases its resistance to changes to voltage. This same pattern is seen for Hj2a, but to a lesser extent, as emphasized by the more limited distance between the blue and gray lines (Chow et al. 2019). The researchers then decided to explore the specificity of activation/inactivation using a technique known as patch/clamp electrophysiology. In this method, the researchers attach a small glass pipette to the membrane of a nerve cell and use this connection to pass signals through the nerve cell (Molecular Devices 2025). The researchers found that the inactivation was subtype specific, with Hj1a primarily impacting channels 1.4 and 1.5, and to a lesser extent, 1.1 and 1.6. Hj2a also showed favorability for channels 1.4 and 1.6, and to a lesser extent, channel 1.1 (Chow et al. 2019). Thus, while both have some impact on channel 1.1, the target channel for DS, they also impact other sodium channels, which could have adverse impacts.

These venom peptides are attractive drug candidates due to their stability and potency, but they lack what is known as subtype specificity (Chow et al. 2019). Essentially, they cannot reliably interact with the specific channel involved in DS without impacting the function of other biologically critical channels. This subtype specificity is one of the biggest features of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs). This, evidently, imposes a key problem in the use of Hj1a and Hj2a as AEDs. However, impacts on other channels may be ameliorated. Both Hj1a and Hj2a show agonistic activity on channels 1.4 and 1.5, which impact the smooth and skeletal muscle and the cardiac system respectively – these application sites are restricted to the peripheral nervous system, and impacts can be avoided by targeting the AED to the central nervous system (Chow et al. 2019). Channel 1.2 poses more problems as it is part of neuronal cells, thus pharmacological activation of this could cause similar symptoms to a gain-of-function mutation, including the early onset of severe epileptic encephalopathies (a disease that impacts the brain) (Chow et al. 2019). Since Hj2a does not affect channel 1.2, researchers are evaluating this peptide further and will need to conduct additional structural analyses.

Ultimately, while neither are truly effective AEDs for DS in their present form, venom peptides provide a basis for the investigation of dual modulatory scorpion peptides. Based on the study by Chow et al. (2019), there is a possibility that, with further modification and future study, venom peptides may be able to help ameliorate the symptoms of DS, which have resisted current treatment methods.

(Adapted from Chow et al. 2019)

References:

Dravet Syndrome Foundation: “What is Dravet Syndrome?”; no date [accessed December 15, 2025]. https://dravetfoundation.org/what-is-dravet-syndrome/.

Molecular Devices: “Patch Clamp Electrophysiology”; no date [accessed December 15, 2025]. https://www.moleculardevices.com/applications/patch-clamp-electrophysiology.

Chow, C. Y., et al. (2019). “Venom Peptides with Dual Modulatory Activity on the Voltage-Gated Sodium Channel NaV1.1 Provide Novel Leads for Development of Antiepileptic Drugs.” ACS Pharmacology & Translational Science 3(1): 119-134.

Escayg, Andrew, and Alan L Goldin. “Sodium channel SCN1A and epilepsy: mutations and mechanisms.” Epilepsia vol. 51,9 (2010): 1650-8.