Every year, over 280,000 tons of synthetic dyes are introduced into aquatic environments as wastage from textile mills. This significant amount of runoff accounts for the augmentation of environmental contamination in several countries, including China, and can have detrimental effects on aquatic life. For example, decreased red blood cell count has been observed in mosquitofish, and liver degeneration in Mozambique tilapia (Dutta et al. 2024).

Previous studies have attempted to use polyacrylamide hydrogels to selectively remove contaminants from an environment. However, the process of creating these hydrogels was found to be too complex and therefore impractical for real-world applications (He et al. 2021). Cheng et al. describe a sodium alginate hydrogel with increased selectivity to a pollutant, malachite green (MG) dye, and heightened adsorptive properties through enhancement with magnetic and MOF materials.

Metal-organic frameworks, or MOFs, are a class of crystalline materials that are made up of a metal ion or cluster and organic linkers. They are extremely porous (~90% free volume) and have extremely high internal surface areas (beyond 6000m^2/g) (Zhou, Long, Yaghi. 2012). These properties, along with the adjustability of their composition, have made MOFs of interest for applications as high-capacity adsorbents for pollutants.

To create their MOF, the researchers dissolved two metal solids, FeCl3·6H2O & FeCl2·4H2O, in water and ethanol, centrifuged, and collected Fe3O4 nanoparticles. They then added another hydrated metal, ZrOCl2·8H2O, and TCPP (the organic linker) to the solution, washed with DMF solvent to dissolve the metals and linkers, and obtained their MOF: Fe3O4@MOF-545 with an average particle size of 1100nm.

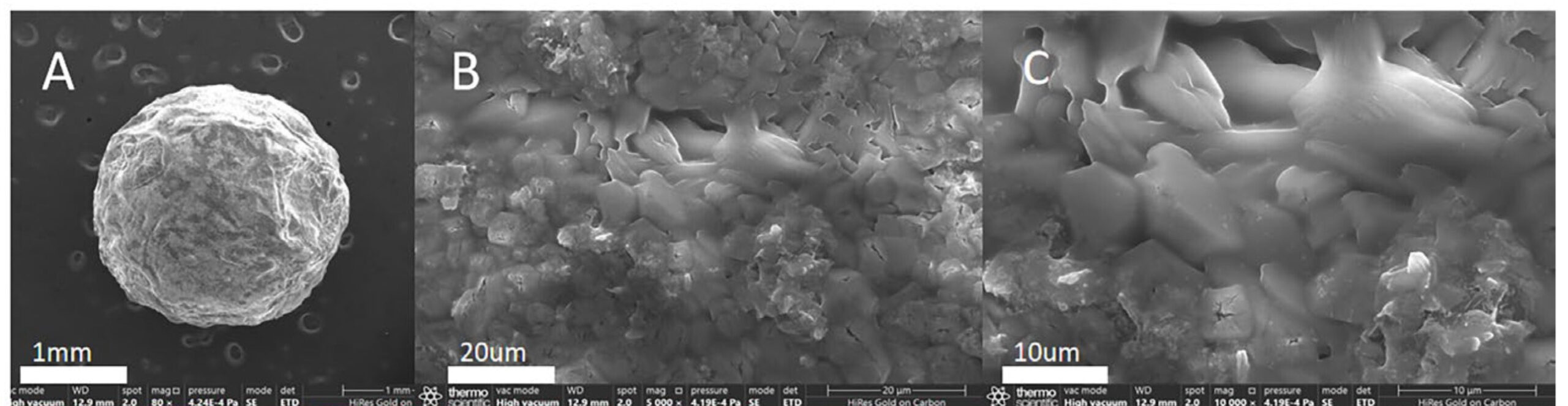

Next, they created a solution of their MOF, 4.2% sodium alginate, TEMED, and acrylamide to form the polyacrylamide hydrogel. The resulting solution was added drop-by-drop to a CaCl2 solution to form microspheres and stirred magnetically for an hour to obtain the MMOF hydrogel (magnetic MOF hydrogel). The researchers used scanning electron microscopy to characterize the MMOF hydrogel and found that the MMOF hydrogel had a microporous structure and clear surface grooves, enhancing its surface area and adsorptive capacity. (Figure 2)

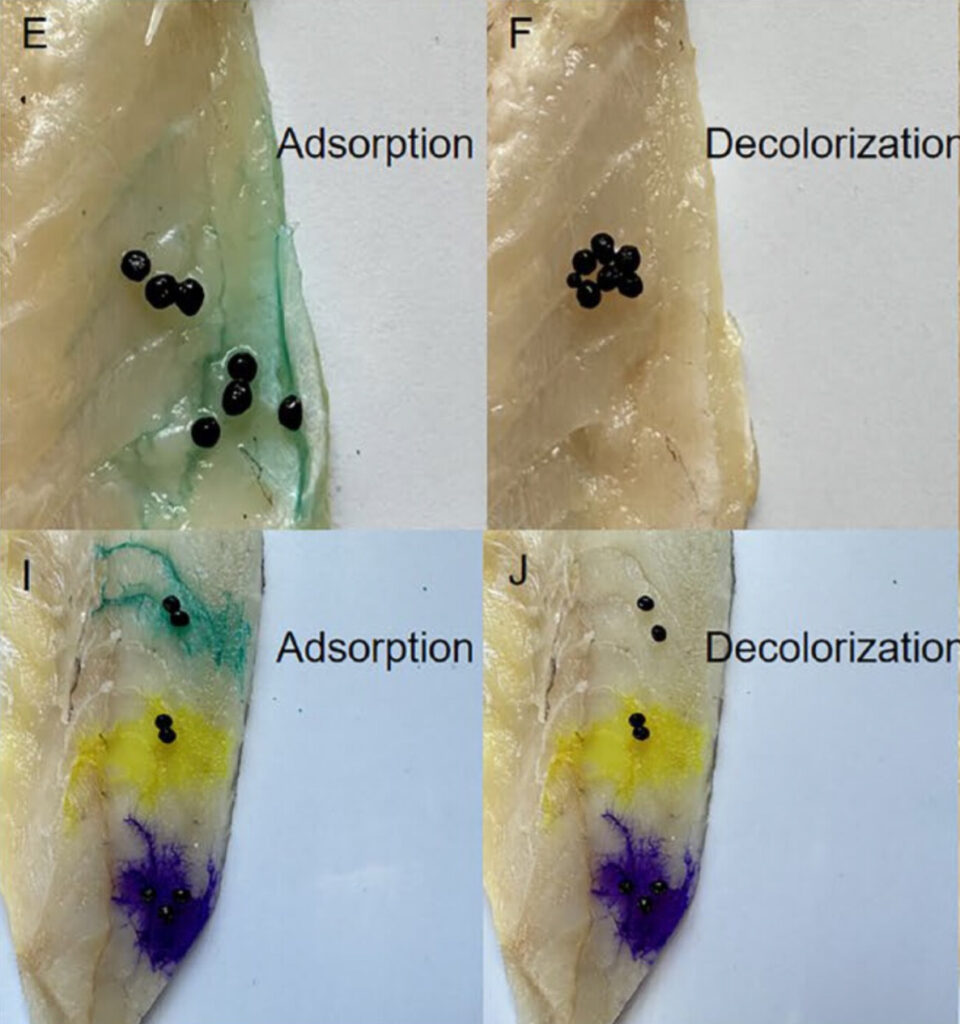

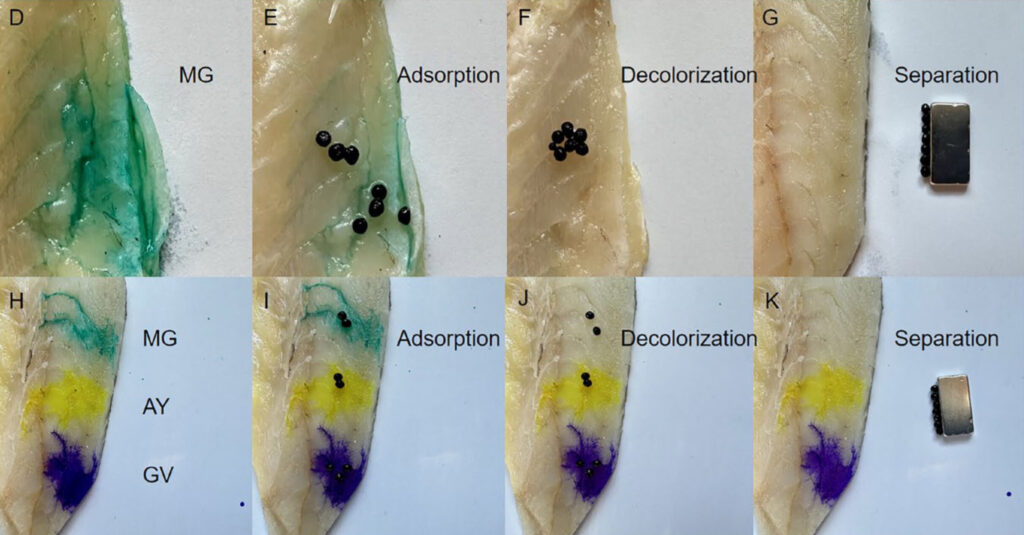

To confirm the heightened performance of the MMOF hydrogel, the researchers compared its dye adsorption and selectivity for MG dye compared to a magnetic hydrogel and a pure hydrogel. The resulting MMOF hydrogel was found to be a significantly more effective adsorptive agent for MG dye than the other types of hydrogels (Figure 3), further showing the effectiveness of MOFs in increasing adsorption. The MMOF hydrogel also displayed enhanced selectivity to MG dye when applied to the surface of aquatic tissues in situ (Figure 4).

Cheng et al. then tested MMOF hydrogels with different characteristics to find material and environmental conditions for optimal adsorption. They found that sodium alginate concentration and MOF:hydrogel weight ratio were associated with the adsorptive capacity of the MMOF hydrogels. The optimal sodium alginate concentration was found to be 4.2%, and the optimal MOF:hydrogel weight ratio was found to be 12.

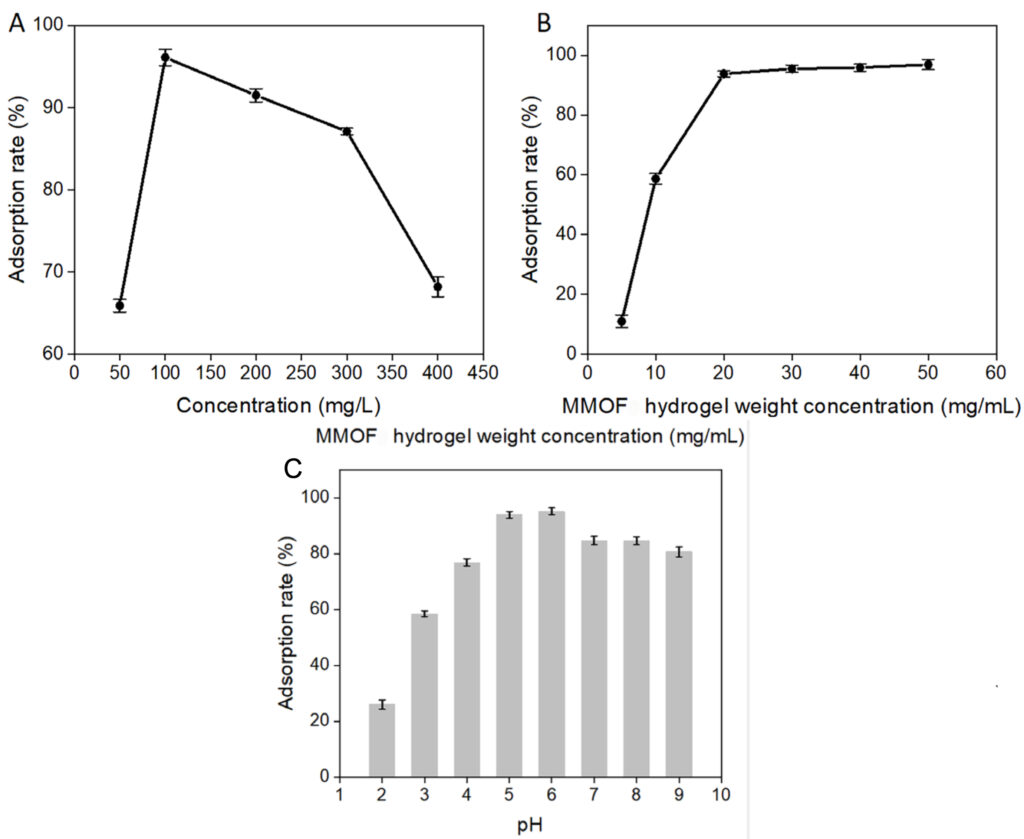

The researchers also tested the MMOF hydrogel in different environmental conditions to determine its limitations and where it performed best. They observed that the MMOF hydrogels showed the greatest adsorption at an MG dye concentration of 100mg/L (Figure 5A). This is due to the increased competition of MG molecules for adsorption sites on the surface of the MMOF hydrogel at higher concentrations. They also found that adsorption plateaued at MMOF hydrogel weight concentrations higher than 20mg/mL (Figure 5B) due to the adsorption sites on the hydrogel reaching equilibrium. Additionally, adsorption was highest at an MG solution pH of 6 (Figure 5C). At lower pH, H+ ions would compete with MG by due to the negatively charged functional group on the MMOF hydrogel. At higher pH, the carboxyl group on the MMOF hydrogel is ionized, decreasing the adsorption rate of MG dye. The adsorption rate of MG dye by the MMOF hydrogel was also found to show little decrease after 25 days of storage at 60ºC, indicating the strong stability of the material.

In their work, Cheng et al. have successfully created stable and easy-to-replicate MMOF hydrogels showing high adsorptive capacity and selectivity to MG dye for aquatic tissue in situ. The easily modifiable structure of MOFS also opens the door to the production of MMOF hydrogels selective to other dyes as well. This research has great potential applications for the pretreatment of aquatic products like fish before they reach the market. If automated and integrated into the screening processes of aquatic products, these MMOF hydrogels could strengthen quality control and increase the safety of products that are entering the market.

References

Chen, H., Brubach, J.-B., Tran, N.-H., Robinson, A. L., Ferdaous Ben Romdhane, Mathieu Frégnaux, Francesc Penas-Hidalgo, Solé-Daura, A., Mialane, P., Fontecave, M., Dolbecq, A., & Mellot-Draznieks, C. (2024). Zr-Based MOF-545 Metal–Organic Framework Loaded with Highly Dispersed Small Size Ni Nanoparticles for CO2 Methanation. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 16(10), 12509–12520. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.3c18154

Cheng, L., Lu, Y., Li, P., Sun, B., & Wu, L. (2025). Metal–Organic Framework (MOF)-Embedded Magnetic Polysaccharide Hydrogel Beads as Efficient Adsorbents for Malachite Green Removal. Molecules, 30(7), 1560–1560. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30071560

Dutta, S., Adhikary, S., Bhattacharya, S., Roy, D., Chatterjee, S., Chakraborty, A., Banerjee, D., Ganguly, A., Nanda, S., & Rajak, P. (2024). Contamination of textile dyes in aquatic environment: Adverse impacts on aquatic ecosystem and human health, and its management using bioremediation. Journal of Environmental Management, 353(120103), 120103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.120103

Zhou, H.-C., Long, J. R., & Yaghi, O. M. (2012). Introduction to Metal–Organic Frameworks. Chemical Reviews, 112(2), 673–674. https://doi.org/10.1021/cr300014x