To most people, the phrase “death prediction” conjures distant images of glowing crystal balls, vibrant tarot cards, or the mystical fortune tellers in popular movies like Big and Ghost. Despite the terrifying implications of a finite and predictable death, a societal obsession with it pervades our media, culture, and everyday life. Though death prediction has historically been confined to fiction and spirituality, scientific advances are transforming it into an imminent next step.

Until the early 2010s, death prediction in the scientific sphere was limited to chronological age. The basic understanding that humans are more likely to die as they reach the end of their average life span was, and still is in many ways, the foundation to any scientific attempts to predict mortality (Gaille et al.). However, more recently, researchers have discovered observable markers of “physiological age”, or traits independent of chronological age that indicate when an individual organism is near the end of its life. In a 2012 experiment, scientists Rera et al. found a reliable predictor in the model organism Drosophila melanogaster, otherwise known as the common fruit fly. According to the study, the flies enter an identifiable “pre-death stage” marked by an increase in intestinal permeability, which can accurately predict when they are near the end of their life. Increases in intestinal permeability were tracked by injecting the drosophila flies with a non-digestible blue dye and observing if their intestinal walls allowed the dye to pass through, causing them to externally turn blue (in drosophila with normal levels of intestinal permeability the dye remained confined to the digestive tract). The high intestinal permeability associated with the blue flies and pre-death stage was appropriately dubbed the “Smurf phenotype”.

Drosophila with the Smurf phenotype were observed to have significantly lower remaining life spans than their age-matched non-Smurf counterparts. While the link between intestinal dysfunction and approaching death is still not fully understood, recent data point to changes in immunity-related gene expression and the aging fly’s microbiome as potential causes. These changes can be caused by old age or other afflictions; in the Smurf flies who were significantly below the average lifespan of the species, other morbidities were often observed, such as mitochondrial dysfunction, increased internal bacterial load, and insulin resistance syndrome. Evidently, the flies’ transition to their “pre-death stage”, or the Smurf phenotype, is a more accurate and comprehensive predictor of death than chronological age (Rera et al.). This biological phenomenon was later observed in other animals too, notably zebrafish and nematodes (Gaille et al.). The prevalence of this observable transition in multiple organisms coupled with its accuracy is slowly but surely turning mortality prediction into a reality.

Surprisingly, death prediction in humans is not far off from the developments seen in Drosophila and other model organisms. In a 2019 UCLA clinical trial, scientists tentatively proved that intestinal permeability is linked to approaching mortality in humans. While the trial was small and needs to be replicated, it provided significant evidence that the efficacy of intestinal permeability decline in death prediction has significant potential for human mortality prediction (Angarita et al.).

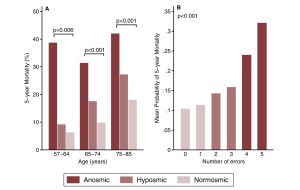

Outside of intestinal permeability, scientists have discovered alternative ways to predict a pre-death stage in humans. In a 2014 study, Pinto et al. theorized that olfaction could serve as another indicator as it relies heavily on peripheral and central cell regeneration, which tend to degrade near the end of an individual’s life due to old age or other morbidities. In the study, roughly 3,000 adults in the age range of 57-85 were asked to identify five different common odorants via forced choice. After 5 years, scientists collected data on which subjects were still alive, and analyzed the connection between their olfactory capability and mortality within the 5 year span. The findings were startling: the mortality rate was four times higher for adults with complete loss of smell than adults with fully intact senses of smell (Pinto et al.).

A: Olfactory dysfunction versus 5 year mortality separated by age group

B: Progression of errors in scent identification versus 5 year mortality (Pinto et al.)

While other methods of death prediction such as biomarkers, genetic screenings, and

demographic studies exist, the discovery of pre-death indicators like intestinal permeability and olfactory decline grant us a unique and improved perspective on mortality. As research continues to grow on this subject, we must question the implications these developments have on our society: how will we reckon with the seemingly impossible ability to predict the future? Is it possible to enjoy life with an exact knowledge of its end? How will both health and wealth inequalities affect the commercialization of testing for death prediction? The moral and ethical dilemmas arising from this development are boundless.

Though these questions do not have finite answers, they must remain present in our discussions of death prediction. While scientific innovations like mortality predictors hold great promise in advancing society, they also have the capacity to exacerbate inequity and other social ills. As rapid development continues to occur in the scientific world, we must maintain both an open mind and an understanding of the complex challenges change poses to our world.

Works Cited

Angarita, Stephanie A. K., et al. “Quantitative Measure of Intestinal Permeability Using Blue Food Coloring.” Journal of Surgical Research, vol. 233, Jan. 2019, pp. 20–25. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2018.07.005.

Gaille, Marie, et al. “Ethical and Social Implications of Approaching Death Prediction in Humans – When the Biology of Ageing Meets Existential Issues.” BMC Medical Ethics, vol. 21, no. 1, Dec. 2020, p. 64. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-020-00502-5.

Pinto, Jayant M., et al. “Olfactory Dysfunction Predicts 5-Year Mortality in Older Adults.” PLoS ONE, edited by Thomas Hummel, vol. 9, no. 10, Oct. 2014, p. e107541. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0107541.

Rera, Michael, et al. “Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction Links Metabolic and Inflammatory Markers of Aging to Death in Drosophila.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 109, no. 52, Dec. 2012, pp. 21528–33. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1215849110.

Cover Image Credit: https://www.npr.org/2019/07/26/745361267/hello-brave-new-world