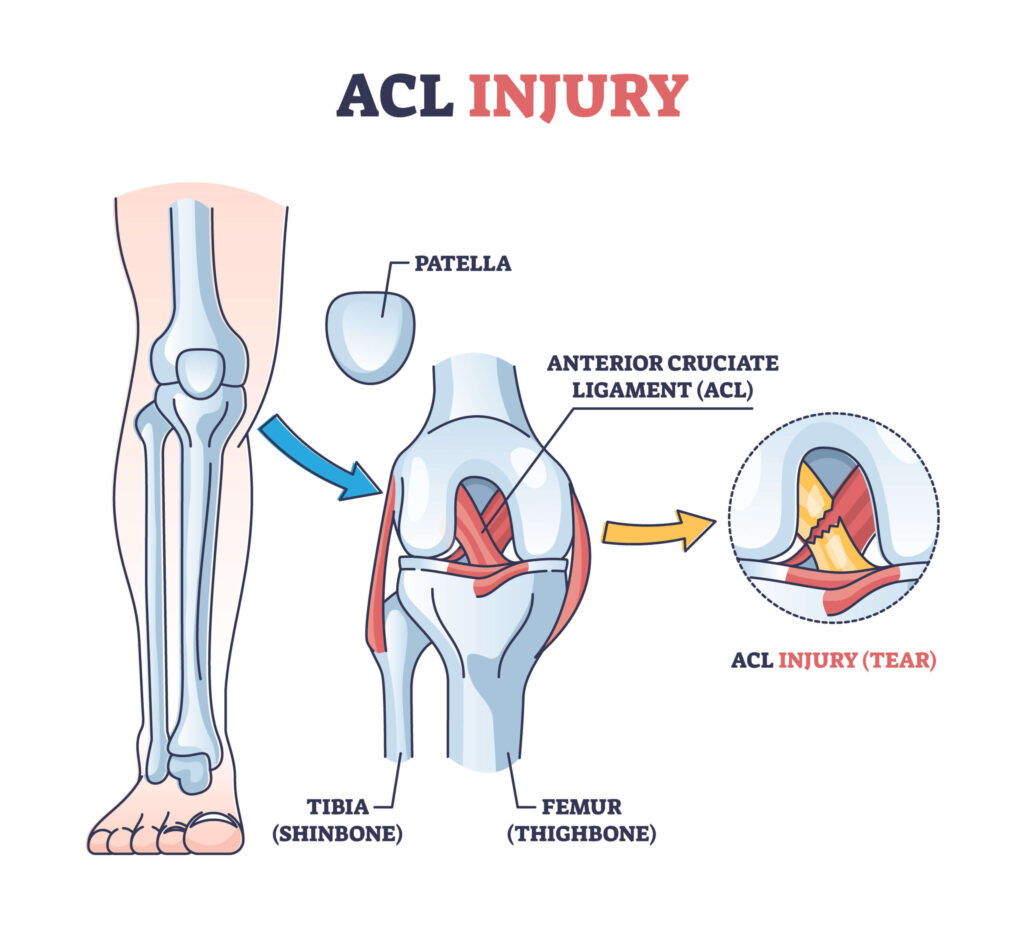

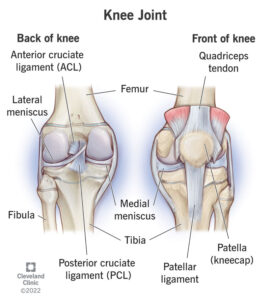

The knee, one of the major joints of the body, powers athletes in their endeavors; it is made up of three bones (the femur, tibia, and fibula), which are scaffolded by a milieu of muscles and ligaments. Injuries most often occur on this scaffolding. A particularly devastating injury is the tear or partial tear of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL). This ligament is tasked with holding the femur and the tibia together and preventing excessive rotation and forward slipping. ACL tears happen when an individual pivots or puts too much sideways pressure on the knee(Knee Joint).

Unfortunately, female athletes are disproportionately affected by this injury in comparison to their male counterparts. In part, it is due to anatomical differences in the alignment of the leg bones. For example, female pelvises tend to be wider, which increases the Q-angle (the angle between the quadriceps and the patellar tendon). This predisposes the knee to collapse inward and give way to ACL tears. However, this is not the only factor on a small scale; hormones are also to blame. In turn, it seems as though the menstrual cycle has an impact on the ACL’s propensity for injury in women(Why Do Young Female Athletes Face Higher Risk for ACL Injuries?).

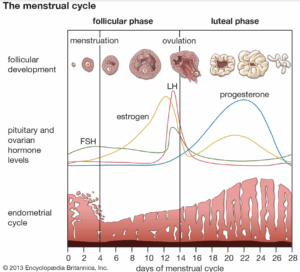

The menstrual cycle is a 28-day hormonal cycle that governs female reproduction. It is made up of 3-4 phases: menstrual, follicular, ovulation, and luteal. The follicular phase and the menstrual cycle are often grouped. Throughout the cycle, different hormones ebb and flow. The main ones are FSH (follicle-stimulating hormone), LH (luteinizing hormone), estrogen, elastin, and progesterone. These are all hormones that are responsible for moving the menstrual cycle along, ranging from the release of the egg from the ovary to the thickening of the endometrium. For example, estrogen is responsible for triggering the thickening of the uterine lining and the release of the egg from the ovary (Wojtys et al., 1998).

Wojtys et al. investigated whether the menstrual cycle phase actually had anything to do with ACL tear risk, especially since most earlier studies focused only on structural differences between male and female knees. The athletes they studied were mostly in their mid-20s and played sports like soccer, basketball, volleyball, track, gymnastics, and skiing—all activities where non-contact ACL tears are common. Each woman filled out a questionnaire that asked about her menstrual cycle (things like typical cycle length, when her last period started, whether she used birth control, and whether her cycles were regular) as well as the exact situation in which the injury happened. Only women with consistent, regular cycles were kept in the sample, which left them with 29 usable responses (1998).

What they found from all this was a clear correlation between menstrual cycle timing and ACL injury, with women most likely to tear their ACL during the ovulation phase, which is when relaxin and estrogen peak. As the name suggests, relaxin is responsible for the relaxation of ligaments and tendons. Outside of the uterus, estrogen is also responsible for the reduction of ACL tensile strength and an increase in laxity. Similarly, relaxin causes a restructuring of collagen, which is theorized to play a role in the susceptibility to ACL injury. (Relaxin.; Wojtys et al., 1998)

An interesting note is that women on oral contraceptives seemed to have lower injury rates. Birth control’s mechanism is stopping ovulation (the phase in which most injuries were observed). Hormonal birth control keeps estrogen levels much more stable by preventing the mid-cycle estrogen surge, so instead of a sharp spike during ovulation, estrogen stays at a steadier and lower baseline. Since that spike is linked to increased ligament laxity, this hormonal stabilization may help reduce the ACL’s vulnerability to injury(Wojtys et al., 1998).

.

This study provides support for the theory that part of the increased likelihood of females for ACL injury, in addition to the mechanical theory, brings forth a hormonal argument. It is worth noting the limitations of the study, however. These are also discussed in the literature itself. The main issue is the accuracy of the self-report. The women were asked at what point they were in their menstrual cycle, as there was no official tracking, there may be inconsistencies here. Moreover, the range in age and level of activity is quite large, especially in such a small sample size (29 individuals).

This type of study can be part of the picture in injury prevention for athletes. ACL tears in particular, are quite devastating injuries. These season enders take 9-12 months to fully heal, in turn barring return to a competitive sport for an extended period of time (Writers, 2021). The consideration of hormonal fluctuations affecting ACL tears can influence training strategies and open the door to understanding oral contraceptives as a preventative measure.

Further directions expanding upon this study could be looking at the menstrual cycle in a more controlled manner, in addition to looking at other connective tissue injuries. Ultimately, the mechanism of soft tissue can be better understood with a deeper view into alternative factors such as hormonal shifts.

References

BCOS. (2023, May 23). What is an ACL Injury? | Symptoms, Causes, & Treatments | BCOS. Burlington County Orthopaedic Specialists P.A. https://burlingtoncountyortho.com/blog/what-is-an-acl-injury/

Knee Joint: Function & Anatomy. (n.d.). Cleveland Clinic. Retrieved December 24, 2025, from https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/24777-knee-joint

Menstrual cycle | Description, Phases, Hormonal Control, Ovulation, & Menstruation | Britannica. (n.d.). Retrieved December 24, 2025, from https://www.britannica.com/science/menstrual-cycle

Relaxin: Hormone, Production In Pregnancy & Function. (n.d.). Cleveland Clinic. Retrieved December 24, 2025, from https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/24305-relaxin

Why Do Young Female Athletes Face Higher Risk for ACL Injuries? (n.d.). Retrieved December 24, 2025, from https://www.cedars-sinai.org/newsroom/why-do-young-female-athletes-face-higher-risk-for-acl-injuries/

Wojtys, E. M., Huston, L. J., Lindenfeld, T. N., Hewett, T. E., & Greenfield, M. L. (1998). Association between the menstrual cycle and anterior cruciate ligament injuries in female athletes. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 26(5), 614–619. https://doi.org/10.1177/03635465980260050301

Writers, Uch. (2021, October 14). How long is recovery time from an ACL tear? UCHealth Today. https://www.uchealth.org/today/acl-tears-how-long-does-it-take-to-recover-and-return-to-sports/