It is estimated that over six million patients seek orthodontic treatment every year to improve their malocclusion, or misalignment of teeth (Hung et al. 2023). Seeing as many people value this treatment, it is not surprising to learn that the way our teeth fit into one another affects the way we eat, talk, breathe, and even our posture. Musculoskeletal (shoulders, spine, muscles) and stomatognathic (teeth, jaws, chewing muscles, tongue, lips) are separate systems of our bodies that interact in intricate ways. For example, a misalignment of teeth alters the muscle-use patterns in our cheeks to compensate for this disparity, which in turn affects the neck muscles which are connected to our face muscles. Through a slight discrepancy in teeth-alignment, the whole head can shift into a different position, impacting one’s health (Bardellini et al. 2022). Unfortunately, the intersection of posture and dental malocclusions is a scarcely researched field. Seeing how impactful dental alignment is to the rest of the body, it is important to research and understand the factors that influence it.

One study published in 2022 by a group of Italian researchers (Bardellini et al.) examined how these systems work together, and the effects of correcting dental malocclusions through orthodontic treatment on the posture of children. While there are many different classifications and types of dental malocclusions, this article specifically analyzes patients using Angle’s classification. Angle’s classification shows three types of malocclusions: class I, II, or III (Fig. 1). Each is described by the position of the lower (mandible) and upper (maxillary) molars. Class I is defined as the molars fitting together in a standard way, however, malocclusions are still present in other teeth besides the molars. In Angle’s class II, the lower molar is farther back (distal) than the upper molar. Lastly, class III shows the lower molar too far in front of the upper molar (Campbell and Goldstein 2021).

The patients that participated in the study were assessed by two clinicians who evaluated their dental occlusions according to Angle’s classification. While deciding which patients to include in the study, the type of dental-skeletal malocclusion within Angle’s classification did not play a role. Most patients observed in this study exhibited a class II malocclusion, followed by class I and III. Patients that had scoliosis, required physical therapy, chronic diseases affecting balance, macro trauma, cleft lip or palate were excluded to ensure that the improvement in posture depended only on malocclusions and orthodontic treatment. Since this study aimed to find a connection between misalignment of teeth and posture in children, the patients belonged to the age group of 9-12 (Bardellini et al. 2022).

Bardellini and her team investigated the postures and weight distribution of patients before and after the treatment using multiple methods, such as vertical laser line (VLL) and stabilo-baropodometric analysis.

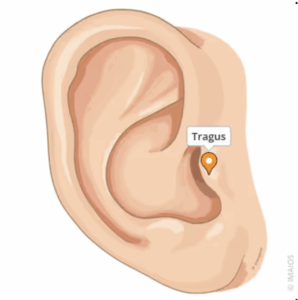

To examine the posture through VLL, the patients were positioned in a standardized position (relaxed posture and arms at side) in front of a white wall. A singular vertical laser line (VLL) was projected onto the patients (Bardellini et al. 2022). The posture was then examined for two factors, the position of the head in relation to the VLL and an excess of extension or flexion. A standard position means the head is centered so that it crosses the tragus—the pointy piece of cartilage close to the cheek (Fig. 2).

If the cartilage did not cross the VLL, the patients’ head was either in a forward or backwards position. Extension and flexion were examined by asking the patients to open their mouths as wide as possible. If the head moved away from the VLL line, it indicated either excess of extension—head bent backwards—or of flexion—the head bent forwards (Fig. 3, Bardellini et al. 2022).

The VLL test indicated that 16 out of 60 patients had a backwards position of the head, 29 a forward position, 10 showed excess of extension while opening their mouths, and 31 an excess of flexion. Only seven patients already had a correct position, meaning that in 75% of patients, dental misalignment influenced head position in relation to VLL line, and 68.33% either flexion or extension.

After determining the posture of the head, the researchers then examined the weight distribution of the participants using a stabilo-paropodometric platform. The patients were asked to stand on a carpet under which a stabilo-paropodometric platform (40x40cm) was placed. The platform measured the typology of the foot and weight distribution across the two feet. The typology of feet can be divided into three kinds: normal, cavus (extreme arch), or flat (underdeveloped arch). Typology can differ between feet, with either both feet showing the same type or different types. The ideal distribution of body weight between feet should be symmetrical at about 50% on each foot (Bardellini et al. 2022).

Through measurements obtained with the stabilo-baropodometric platform, the study found 45 cases (both or one side) with cavus feet, and 6 with flat feet (both sides). Hence, 85% of patients had a typology that incorrectly supported their body. Additionally, about 70% of patients had an unequal weight distribution between their two feet, exacerbating bad posture. An incorrect spread of body weight can be identical on both feet—either too much pressure on the ball of the foot or heel—or it can vary between feet (i.e. one foot shows increased pressure at heel, and the other at the ball of the foot) (Bardellini et al. 2022).

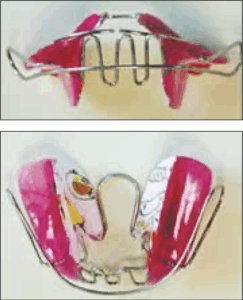

After the classification of malocclusion was identified and the posture (VLL) and weight distributions (Stabilo-baropodometric platform) were measured, the patients were treated with an individually prepared Mouth Slow Balance (Fig. 4), which works by repositioning the tongue, widening the maxilla (upper jaw), and keeping the mandible’s (lower jaw) relation to the maxilla (Bardellini et al. 2019, Bardellini et al. 2022). They describe the MSB device as a “evolution of the Binator”, a retainer like appliance adjusting the bite (Fig. 5, Bardellini et al. 2019 p. 243).

The patients were observed during their treatments for four years (2014-2018), and by the end, 51 out of 60 patients exhibited a correction of malocclusions, either fully aligned or class I (Bardellini et al. 2022). Other patients either dropped out of the study (3 patients) or reached a correction after the observed time frame (6 patients).

Of the 53 patients, 23 obtained the ideal position and 19 saw an improvement but did not complete correction of head-position. In 10 cases, patients were found to have been overcorrected. In the beginning of the four-year observation period, 15 patients had a correct position regarding VLL posture assessment. After treatment, 7 kept their correct position, while 8 now developed a forward position. Additionally, two patients that showed a backwards position before treatment developed a forward position by the end (Bardellini et al. 2022).

Bardellini et al. (2022) also found significant improvements of the posture in VLL open mouth exams. 53.3% now kept their tragus on the laser line while opening their mouths, when they used to hyper-extend or –flex.

53 participants (88%) improved their foot typology, of which 17 achieved a complete correction. Before treatment, only 15% of participants had a “normal” typology, which increased to 28% after treatment. However, weight distribution that varied between feet significantly increased from 18 to 37, of which seven patients developed a weight distribution imbalance they previously didn’t show. Overall, cases also exhibited an improvement without complete correction which decreased the median of support discrepancies over the course of the treatment (Bardellini et al. 2022).

These findings provide evidence for Bardellini et al.’s hypothesis that posture is in fact altered by dental malocclusions. They explain that through a complex chain of muscles across different systems, muscles alter their patterns which disturb the posture, specifically in the position of the head and support of feet. Muscles around our cheeks (masticatory) and neck (cervical) were already discovered to have a connection in previous research (Bardellini et al. 2022). Furthermore, trunk muscles (abdomen, chest, back) are also connected to these muscles. Since the misalignment of teeth affects the so-called mandibular elevator muscles that are a part of our cheek muscles, this change flows over into other muscle systems (cervical and trunk) acting on our posture. Our strategies for balancing are primarily spread across the trunk, head, and pelvis, which means that the misposition of the head leads our body to try and balance it using other methods (trunk and pelvis) (Bardellini et al. 2022). So, the wrong posture shifts the center of gravity.

Although Bardellini et al. have found significant evidence that there is a correlation between dental malocclusions and posture, they acknowledge that they are one of few studies that focus on this specific alteration in posture, hence emphasizing that more research needs to be done.

Furthermore, the results may have been skewed because the team did not consider that the natural changes occurring in growing children may also influence their posture, weight distribution, and more. However, for this specific study it would have been unethical to have a control group of untreated children to compare the effects of treatment vs no treatment (Bardellini et al. 2022).

Bardellini and her team are one of the few trailblazing research articles that examine the impact of malocclusions on posture, specifically targeting the head and feet. As mentioned before, not much research has been done in this field that examines this topic especially, yet it can prove to be vital for child development. Correcting posture early on can improve a person’s life-quality for the rest of their lives, impacting everyday tasks. Hopefully, in the future more researchers will recognize the importance of this subject and contribute new findings.

References:

Bardellini, E., M. G. Gulino, S. Fontana, J. Merlo, M. Febbrari, and A. Majorana. 2019. “Long-term evaluation of the efficacy on the podalic support and postural control of a new elastic functional orthopaedic device for the correction of Class III malocclusion.” European Journal of Paediatric Dentistry, no. 3: 199–203. https://doi.org/10.23804/ejpd.2019.20.03.06.

Bardellini, Elena, Maria Gabriella Gulino, Stefania Fontana, Francesca Amadori, Massimo Febbrari, and Alessandra Majorana. 2022. “Can the Treatment of Dental Malocclusions Affect the Posture in Children?” May 1. DOI: 10.17796/1053-4625-46.3.11

Campbell, Stephen, and Gary Goldstein. 2021. “Angle’s Classification–A Prosthodontic Consideration: Best Evidence Consensus Statement.” Journal of Prosthodontics (United States) 30 (S1): 67–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopr.13307.

Hung, Man, Golnoush Zakeri, Sharon Su, and Amir Mohajeri. 2023. “Profile of Orthodontic Use across Demographics.” Dentistry Journal 11 (12): 291. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj11120291.

IMAIOS. “Tragus.” e-Anatomy, accessed November 20, 2025. https://www.imaios.com/en/e-anatomy/anatomical-structures/tragus-1536888748.

Pakshir, Hamidreza, Ali Mokhtar, Alireza Darnahal, Zinat Kamali, Mohammad Hadi Behesti, and Abdolreza Jamilian. 2017. “Effect of Bionator and Farmand Appliance on the Treatment of Mandibular Deficiency in Prepubertal Stage.” Turkish Journal of Orthodontics 30 (1): 15–20. https://doi.org/10.5152/TurkJOrthod.2017.1604.

Xie, Zhiwei, Fuying Yang, Sujuan Liu, and Min Zong. 2023. “The ‘Hand as Foot’ Teaching Method in Angle’s Classification of Malocclusion.” Asian Journal of Surgery 46 (2): 1062–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asjsur.2022.07.130.